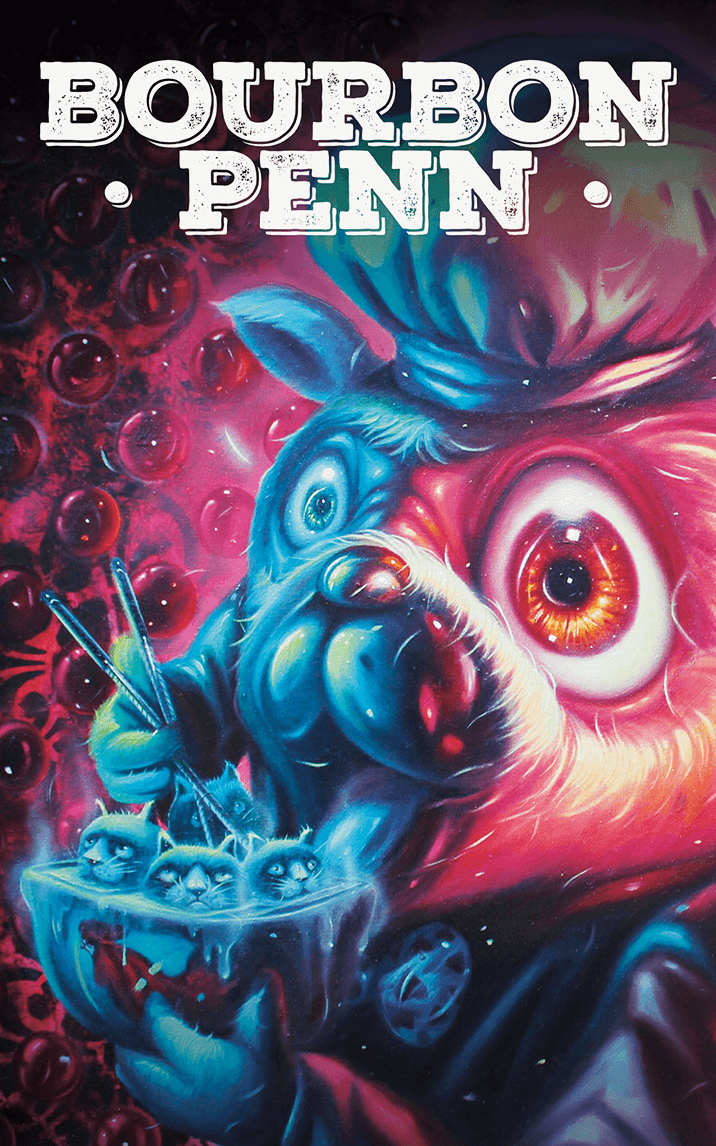

Orange Eyes

by William Jablonsky

1.

It’s mid-September at Lakeview Elementary, 2:35 p.m. It’s warm out and there’s no air conditioning, so Mrs. Palmer’s classroom is hot and stuffy, and all I can do is simmer in my seat and wonder why the pool isn’t still open. It’s time for geography, and Mrs. Palmer has pulled down the yellowed map on the wall. She’s talking about Alaska and the contiguous United States and what it’s like to live there as compared to here, on the Wisconsin side of Lake Michigan, where it doesn’t get as cold and food is cheaper. Jeremy Siegel is picking his nose in the next row over—a championship-level nose-pick, an unbroken suspension bridge of snot from his left nostril to his index finger, a full foot from his face. I’ve dreamt of such an achievement most of my life, and I envy him his seasonal allergies.

This is what occupies me before the creature arrives.

It begins with cracking tree trunks by the lakeshore, falling power lines. From Mrs. Palmer’s window I can only see the foot, dark green and scaly and wet. The metal swingset snaps instantly under its step, then the jungle gym, and the tall slide the fifth-graders jump off to prove our courage. Its feet crush the loose gravel beneath them.

The fire alarm goes off.

“Outside, class,” Mrs. Palmer says. “Walk, don’t run. But walk fast.”

Her skin is colorless, translucent, her big blue eyes wide.

“Just like a fire drill,” she says. “Come on, let’s go. Leave your backpack, Annie. Felix and Doug, stop fooling around. Eyes forward.”

As we round the hallway, the building trembles. And again, and again. The ceiling tiles shake out of place. A few minutes later and we’re all in the parking lot, staring down at the cracked blacktop, the crooked yellow lines cutting off at the edge of pickup-sized footprints. Outside it smells like dead alewife and peat moss. I try to get a look at the thing that made it, but the sun is in my eyes and I can only make out a tall black shadow, moving slowly away. A deep, wet snort rattles the windows. Mrs. Palmer gasps and her hand goes to her heart. Mr. Hale, the principal, makes the rounds outside, counting heads. He’s skeletal and dour, with short silver hair, deep-set eyes, and a long gray face. His hot pink dress shirt makes him look like a walking bottle of Pepto-Bismol. I offer this observation to Mrs. Palmer.

“Not now, Dustin,” she says.

Mr. Hale’s eyebrows crinkle. He does another head count. Some of the teachers are crying. I look around—Miss Crandall, the kindergarten teacher, isn’t there. Her bright-orange pageboy haircut should be visible from near-orbit.

“Damn it,” he says.

I chuckle. He’s not supposed to say things like that. Mrs. Palmer slaps my shoulder. Under the circumstances, best to let it go. I’ll bring it up when and if the situation demands.

After a few minutes the shadow is gone, the rumble recedes. Mrs. Palmer tells us the emergency alert system has phoned our parents and they’ll come for us shortly. Mr. Hale whispers something in her ear. She begins to cry.

“What happened?” someone asks.

“An earthquake,” she says. “But it’s over now. You’re safe.”

Helicopter rotors sound in the distance, followed by a few dull popping sounds, a bigger explosion. Black smoke rises above the houses.

“What was that?” I ask.

“Nothing,” she says, squeezing my shoulder. “Everything’s fine.”

• • •

The WKTI news van shows up before our parents do. They single out a few of us—the ones cute enough to get ratings but articulate enough to describe the moment. Rachel Kowalski, the prettiest, tallest, and most mature girl in our class, the one who gets the leads in the school plays and Christmas pageants, she who will one day be named prom queen and class president and ruler of the world, is selected first. She is slender and elegant, and as she steps forward all I can do is follow the perfect lines of her shoulders. The reporters shove microphones in her face. She looks into the camera with grace and poise.

“It was a monster,” she says. “A big monster. With dark green scales.”

“But giant monsters aren’t real, sweetie,” one of the reporters says. I recognize her from the local fluff pieces on the TV news, a tall redhead with ample cleavage. Mom once said she could guess how the woman got her job. I assume this means something dirty.

“I know what I saw,” Rachel insists, but the reporter has moved on.

“What do you think, young man?” She pushes the microphone up into Billy Weber’s face.

“It was a kaiju,” he offers. Billy knows far too much about monster movies, dinosaurs and computers, and will either become a billionaire or live in his parents’ basement until he’s forty.

“And that is?” The reporter bends over low and Billy gets a full-on look.

“A giant monster that got mutated from pollution or radioactivity.”

“Well that’s silly,” the reporter says. “There’s nothing like that in Lake Michigan.” She stares blankly, then turns away to find a younger child, one who will give a cuter and more tearful account.

Mom shoves her way through the crowd and grasps me tight, gives me a tearful hug. I’m not sure what’s happening, but I climb into the Buick without fuss. There’s an Adventure Time marathon starting at three, and if we hurry, I can catch all of it.

• • •

Later, on the six o’clock news, a series of experts try to explain what it was. A cyclone, moving west over the lake. A brief and violent thunderstorm. They cut Rachel’s clip but air part of Billy’s. Then it’s another expert with long curly hair tied up in a loose ponytail, who says that while kaiju have been limited to Japan in the past, it is possible something dumped in the lake could cause similar phenomena. I mouth phenomena a few times and deem it good, until Dad tells me to knock it off.

There’s to be a brief memorial for Miss Crandall and the kindergartners lost in the collapse. Mom asks if I want to go, but I was never in her class, and I didn’t know any of the kids, because they were kindergartners and kept to the east end of the playground, as us bigger kids expected of them.

Then the mayor comes on, speaking from the circle drive, flanked by the school district superintendent and some men in lab coats and hard hats, inspecting the scene.

“I think some folks have very active imaginations,” he says. “We don’t have a kaiju problem in St. Francis. It was just a storm. We’ll look into reinforcing the roof in case it happens again.”

Dad nods. “See?” he says. “It wasn’t a monster.”

“But honey …” Mom begins.

“It’s over and our boy’s safe. Right?” He looks to me for validation. I nod and smile brightly, because he wants me to.

“If you need to talk about it,” Mom says, wrapping an arm round me, “we’re here.”

I nod, but there’s nothing to talk about.

2.

It’s late October, and Mom makes me wear my heavy orange coat even though it isn’t that cold. This is an unforgivable show of weakness, so I peel it off on the bus and stuff it in my backpack. I drowse while Mrs. Palmer goes over the Battle of Yorktown, replete with her little chart full of X’s (American-French forces) and O’s (British), and explains how America wouldn’t have won without French intervention. Staring at all the little markings is intolerable, and there’s pounding overhead as the construction crew reinforces the roof. I stare out the window for a while. The lake is grayish-white, choppier than usual.

Something comes out of it—a dark spot where water meets sky, so distant I think it’s a trawler. Then a rush of wind, a pair of dark green wings emerging from the lake before the thing goes airborne. The outline of its sharp, broad wings casts a shadow like a bomber. Billy’s staring too, so it’s not just my imagination.

“Just what is so interesting out there?” Mrs. Palmer says. “Pay attention, people.”

Billy points. She looks. Her face whitens.

“Under your desks,” she says. “Now. Hands over your heads, like you’ve been taught.”

But we can’t. Whatever it is, each beat of its monstrous wings depresses the lake water in its wake. For just a second, I see the dull, dark orange eyes set close together and deep in their sockets, the long beak, the orange horns on top of its head. As it flies toward the school, the beating of its wings knocks limbs out of trees. The kids with smartphones pull them from their backpacks, try to get pictures. I’d do the same, but Mom and Dad took mine after I recorded Mrs. Palmer adjusting her bra strap when she thought no one was looking. Billy records as the dark shadow blocks the sun and fills the window. It flaps its wings once, so forcefully the trees bend. One of the panes collapses inward and shatters on the floor. Something that looks like a man flies off the roof, turns end over end, and lands unmoving in the center of the playground.

Everyone screams, except me.

“Desks! Now!” Mrs. Palmer shouts.

This time we do it.

The roof shakes as it beats its wings again and lets out a shriek that shatters the fluorescent lighting fixtures. Then it’s in the air again, the shadow of its wings darkening the ground outside.

We’re about to get up when something hits the roof above us, hard. Steel girders snap, and then a greenish-brown and pill-shaped mound the size of a compact car drops into the middle of the classroom, spattering on the floor, and walls, and us. Mrs. Palmer is covered in it. The room stinks of sulfur and dead things rotting. I laugh, because we’re covered in shit, and that sort of thing is funny as hell. No one tells me to stop.

Thirty seconds later, the alarm sounds and we are in lockdown. From somewhere over the trees, we hear what sounds like fireworks, which Billy insists is anti-aircraft fire. The ground shakes once, the booming stops, then silence. A few minutes after that, the police arrive, march us out, give us handi-wipes to clear the monster shit from our hands and faces, and wait with us until our parents arrive. They tell us not to look at the tarp-covered figure on the playground. I look anyway. Not as interesting as I’d hoped—just the profile of a man under the plastic.

No one was hurt this time, except for the dead roofer.

• • •

School is out for three days. On the third night, the PTO holds a meeting, and Mom and Dad bring me along to avoid shenanigans. They haven’t trusted me home alone since the bathtub fire, a clumsy attempt to give my G.I. Joes realistic battle damage that went awry.

The gym is full and loud, and I throw old popcorn kernels and bunched-up candy wrappers at people’s heads while the adults argue.

“Something has to be done,” Rachel’s mother says. She’s both the head of the PTO and on the school board, the most important civilian here. “Our kids aren’t safe.”

“The odds of being killed by a kaiju are one in three hundred million,” someone else says. “I Googled it.”

“The superintendent tells us he can’t do anything more,” Mrs. Kowalski says. “I don’t accept that.”

“Arm the teachers!” a man in a Brewers cap yells from the bleachers. “Next time one of those things shows up, they can blow that sum’bitch straight to hell!”

“That’s ridiculous,” Rachel’s mother says. “You want them to fight giant monsters with … what, pistols?”

The man stands up. “I guess you don’t care about keeping our kids safe.”

“That’s the only thing I care about,” Mrs. Kowalski says. “Maybe it’d be better to figure out where those monsters are coming from and take care of it at the source.”

“I agree,” says the man with the curly ponytail. He looks like a homeless person in a lab coat. I laugh accordingly. Mom shushes me.

“I studied that first one,” he says. “There were traces of toxic waste in its cells—just the kind the coal plant has been dumping in the lake.”

“Now hold on a second,” the mayor says. “That’s an unrelated matter.”

“Really?” the curly-haired man says. “You’d rather let those things keep smashing up the school than actually stop the cause of the problem?”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” the mayor says.

“I know better than most,” the curly-haired man says. I dub him Professor Curly. “If you read my report, you’d know it too.”

The mayor loosens his tie, and it looks like they’re about to throw down. This should be good.

“All you goddamned liberals from the city think you know more than the rest of us who live here.”

“Maybe if you’d paid more attention in school, you might know dumping all that shit in the lake has consequences,” Professor Curly says.

“Fuck you,” the mayor says.

“And fuck you as well, sir,” Professor Curly retorts.

Mom covers my ears for the rest. But when you have parents who whisper about you like you’re not there, you get good at lip-reading.

This is how the meeting ends.

“Nobody’s going to do a thing,” Mom says on the way home. “Just like always.”

“That scientist guy was just fear-mongering,” Dad says. “Just a couple of isolated incidents, like the mayor said. Probably won’t happen again.”

“I don’t understand how you could’ve voted for that man,” Mom says.

Dad’s about to say something, but he looks back at me in the rear-view mirror and his lips clamp shut.

They don’t talk the rest of the way home, but after I’m in bed I hear the whispered argument from the living room.

3.

At a closed-door meeting, the school board decided that Mr. Corvis, the seventy-year-old custodian, is the solution, because he used to be a Marine and fought in some war in the early seventies. At the beginning of the school year he took all the Latino kids aside and asked if they were legal. I once repeated some of the names he called them, and Mom made me wash my mouth out with soap.

The day after the board meeting, there’s an assembly outside. Two tall clay sculptures stand at the edge of the playground, maybe twenty feet tall, the big ones each class made last year in art class before the art teacher got laid off. One is a baby-blue T-Rex with red eyes—Tommy T-Rex, we’d christened him—the other a giant green lizard with a frog’s head who we’d named Lester. We’d worked hard on those. They’d been displayed at city hall and were supposed to be auctioned off to raise money for the school.

Mr. Corvis is holding a big, heavy black gun with a wide, gaping barrel. Reporters and parents are scattered around the playground, news vans parked along the curb. The mayor puts his arm around Mr. Corvis and smiles while photographers from the Journal-Sentinel take his picture. “I promised you a solution, and here it is. If one of those things starts prowling around here again, we’ll be ready. All set, Mr. Corvis?”

Mr. Corvis nods, aims, fires. The report is a low pop, not the boom I was expecting. Tommy T-Rex flies apart in a hail of fire and smoke, little glowing papier-mâché fragments showering over us. Most of us cheer, myself included—this is much better than the lackluster fireworks display on the Fourth of July. A few of the artsy girls cry over the sculptures, oblivious to the spirit of the moment. Mr. Corvis reloads, does it again, this time blowing the head off Lester. Its legs and tail smolder in the breeze. Though I’m sad to see Tommy and Lester go, I secretly hope another monster stumbles out of the lake, because then there’ll be a show. I’d love a nice monster jawbone to hang on my bedroom wall. Or even just a tooth, or a scale.

Professor Curly is there, too. He shouts to the reporter that he’s got documentation tracing the monsters directly to the coal plant. But amid the smoke and embers, no one listens.

4.

It’s late February, and thus far I’ve been cheated of the spectacle of exploding kaiju guts. The mayor has gone on TV twice and proclaimed that his idea of arming Mr. Corvis has deterred future monster attacks. I wonder how they know Mr. Corvis is packing a grenade launcher, but Dad tells me the situation is well in hand. Billy says it’s been too cold—the creatures are mostly cold-blooded and inactive in winter. Comments like that take all the fun out of it. But near the end of the month, the weather warms up, and the foot-high snow on the playground turns to slush and melts away. This, Billy says, cannot be good.

On the last day of the month it’s almost seventy degrees. I’m busy pelting Billy with little bits of gravel at recess when I hear the massive scraping of rock and soil, as if someone is excavating with a bulldozer. At the lakeshore, a shadow: dark green, almost black, a greenish-brown dome rising above the ash trees that splinter under its weight. It trudges along like a snail, then stops, a small head rising into the air, a single red-orange eye surveying the school grounds, the playground, us. Slowly, it heads our way, each step shaking the ground. As it approaches, I catch a closer look: a snapping turtle from hell, skin streaked with glowing yellow veins, sharp, curved protrusions all over its face, orange eyes fixed on the new kindergarten wing. Mrs. Palmer and the other teachers quickly shepherd us away to the far edge of the school grounds by the cornfield, a safe distance from which to watch the show.

“Don’t worry,” someone says. “Mr. Corvis will handle it.”

He hasn’t yet arrived by the time the creature rears on its hind legs, props itself against the building, and begins to grind its lower half against the outer walls.

“What’s it doing?” Rachel asks.

Billy chuckles, and I finally catch on.

“Oh, my,” Mrs. Palmer says. “Turn away, children.”

“Is it boning the school?” I ask.

“Yes,” Mrs. Palmer says. “And don’t say that. It’s vulgar.”

Finally, Mr. Corvis emerges from the fourth and fifth-grade exit, the long metal tube over his shoulder. He takes careful aim, pulls the trigger. There’s a pop. We watch and wait for the promised explosion of blood and turtle guts. The grenade explodes against the creature’s shell without even leaving a fissure. It grunts once, then resumes thrusting.

Mr. Corvis loads another round, gets closer, fires again. This time the grenade hits the creature’s undershell. Still nothing, though it stops for a moment to stare down at him. He fires once more as it’s finishing its business, then it trudges after him with a low grunt.

“Oh, shit,” he says, loud enough for us to hear. A couple of kids giggle at him swearing. It’s not even the worst thing I’ve heard him say.

In three steps it’s on him. Mr. Corvis fumbles the last round as the ovoid shadow eclipses him, then disappears under the creature’s massive foot. It walks away toward town, leaving a reddish-pink smear in the grass.

Mrs. Palmer is too stunned to tell us not to look.

• • •

The mayor calls another town hall the same night, this time at the orchestra shell at Nimbley Park, on a bluff overlooking the lake. My parents drag me there again, to avoid the aforementioned shenanigans. The mayor’s white pompadour is higher than usual, his grin forced. He’s flanked by the pastor of the church two blocks down from the school, Superintendent Grossman, and two men in sheeny charcoal suits and short haircuts, who take turns whispering in his ear. He taps the microphone, leans in.

“I’d first like to extend our thoughts and prayers to Mr. Corvis’s family. He died a hero.”

“So, what are we supposed to do about the school?” Rachel’s mother asks.

Superintendent Grossman steps in. “We’re going to thoroughly power wash the east wing and reinforce the walls. Until that’s done, some of the classes will be relocated to the cafeteria and the gym. The custodial staff are moving the desks as we speak.”

“And how do you plan to deal with the monster problem? Your last solution didn’t work so well, and now the janitor’s dead.” I look over the gathered crowd: it’s Professor Curly again. He’s wearing thick, square-rimmed glasses, a folded bundle of papers in his hand.

“Christ, not you again,” the mayor says.

“I’ve got lab reports from the first two kaiju—the flying one and the big lizard-frog thing. They both show high levels of a compound called X29 in their cells. My graduate students and I traced the X29 leakage right to the coal plant just down the shore. They use it for …”

“I don’t have time for this right now, son,” the mayor says. “I’ve had enough of you lab coats coming down here and spreading your fairy tales.”

“When are you going to fix the root problem, Mr. Mayor? No more X29, no more kaiju.”

“They are not kaiju,” the mayor says. “That’s a Japanese problem. This is America, in case you’ve forgotten.”

A few people in the front row, mostly older men in camouflage ball caps, hoot and holler. Mom glances over at Dad, eyebrows raised. I don’t understand why, and I don’t care because this is hilarious.

“You’re obfuscating. Are you going to deal with the problem or not?”

The mayor laughs. “You hear that? I’m obfuscating. Speak English, son.”

“You understand me just fine.”

The mayor sighs. “That plant employs fifteen hundred people. And X29 is a proprietary formula. You really want to risk all those jobs on your B-movie theory?”

“It’s called science, sir. And isn’t your family part-owners of that plant?”

The mayor shrugs, then lots of people shout swear words back and forth. Professor Curly is escorted out by the men in sharp suits.

“You didn’t answer his question. How do you plan to deal with this?” It’s Rachel’s mom again, tall and perfect and beautiful like Rachel, but even more so.

The mayor sighs, forcibly pulls Superintendent Grossman to the podium.

Grossman looks around, nervous, clears his throat. “In consultation with Mayor Bixby, we’re hiring three additional school resource officers. They’ll have state-of-the-art weapons and advanced kaiju response training. Your kids will be safe from now on.”

“You keep saying that,” Rachel’s mom says, pointing her finger like a stiletto blade. “I’m not sure I believe you.”

• • •

Two days later, the school has a memorial gathering for Mr. Corvis. Dad drags me against my will, because he says I ought to pay my respects. Hardly anyone else is there. Maybe it was all those things he said about Mexicans.

5.

It’s late March, just before Easter break, and only a few clumps of wet snow remain on the ground. I’m bored of geography and American government and beginning algebra. Several seats around the room are empty—Rachel’s mom transferred her to an arts school in downtown Milwaukee, and the room is dimmer for her absence. Billy’s parents decided to home-school him—so it’s his parents’ basement for him from now on. And Jacob’s parents moved out of state, to, as he put it, get him away from this godforsaken shithole. Dad says they’re being cowardly; we’re made of sterner stuff.

There’s a sound outside like a bomb exploding underwater. A waterspout shoots up from the lake like a geyser. Then, a thud like a small earthquake, the tips of an immense forked tail rising above the treetops and falling with a plume of spraying water that taps on the windows like rain. For a minute or two after, there’s no movement, only a long silence. A fishy smell comes through the window. Mrs. Palmer closes it.

“Back to your spelling, everyone,” she says. But she keeps glancing toward the window, toward the gap in the trees, waiting for something to emerge.

Out the window, the three school resource officers, weapons drawn, inch slowly toward the lake. It’s the most exciting thing that’s happened here in weeks. About ten minutes later they come back. Officer Schlosser gives the all-clear sign to Mrs. Palmer and smiles.

• • •

It isn’t until we’re eating chicken fingers and fries on the couch that we find out it was a seventy-five-foot mutated Coho salmon, orange horns protruding like daggers above its eyes, a glowing, barbed tongue like a mace. It leapt out of the water and flopped its way onto the beach, then died after about fifteen minutes. The pictures are all over the news. I watch Professor Curly and a few grad students in waders and rubber gloves try to collect tissue samples, but the mayor and the two suits block him with their bodies. The close-ups are hypnotic: the creature’s sharp orange eye, big enough for a grown man to lie across, flecked with green and black speckles, the long slit of an iris like a maw that could devour me whole.

No one was hurt this time, so there is no need for another emergency meeting.

“Maybe it’s time we moved to Minnesota,” Mom says, quietly, as if I can’t hear.

“It’s fine,” Dad replies. “The officers did their jobs.”

“The thing died on its own.”

“We can’t let something like that drive us out of our home,” Dad says. “What would that say about us?”

“That we care about our child?” Mom’s voice is high and squeaky, like when she told me Grandpa was dying of heart failure.

“They’ve got it. It’s handled.” Dad gets up in a huff and shuffles into the kitchen for a beer. Mom wraps me in a tight embrace. But my eyes stay fixed on the TV and that giant, terrible eye.

6.

It’s late May, two weeks from summer vacation, and I silently dream of diving out the window to run in the field outside. Dad’s threat of withholding my pool pass this year keeps me in my seat. My legs twitch. I look across the room at the empty desks—almost half our class is gone. Max’s parents moved him to the Christian school in the old Piggly Wiggly. Rosie and Alexis, the twins in floral sundresses and elaborate braids, transferred to a school up in Cudahy. Courage is a rarity these days.

Mrs. Palmer calmly goes over etiquette for our field trip to Great America next week—a chance to blow off steam at the end of the year, which we could all use. None of us are to leave her sight.

It seems fair, considering.

From outside comes a sound like a giant meteor crashing into the lake, a plume of water erupting over the treetops, droplets flying like glitter. The floor vibrates beneath my canvas sneakers.

“Oh, Jesus,” Mrs. Palmer says. “Not again.”

She tells us to head for the doors. I glance outside to see if I can catch a glimpse: The three officers in their tactical gear sprint toward the lake, unsling the grenade launchers from their backs. I stop to watch. This should be spectacular.

Then, something rises from behind the trees. The officers stop cold.

It’s big, twice the size of the others, greenish-black like decaying leaves, with a head like a raptor and the body of a man, with those same terrible red-orange eyes. It stares past the trees and the officers, right into our classroom window. It steps forward, trudges past the pier, up the embankment. Its shadow darkens the room.

The other two officers run, but Officer Schlosser raises his weapon and fires. There’s some smoke and a brief flash, but the creature doesn’t even slow down. He fires again. And again. And again. The creature opens its mouth; something bright orange burbles in its throat and sprays like glowing vomit. And then there is only a blackened pit where Officer Schlosser used to be.

“Outside,” Mrs. Palmer says calmly, but no one can move. Not even her.

The creature roars, a deafening shriek that shatters the windows and light fixtures. I can only see its legs up to the knees, its algae-green claws turning up dirt with each step. Then it halts, leans down, peers in through the window, sniffs the air, exhales. Its breath smells like burning lake mud. It blinks once. I can’t look away. For the first time, I wonder if this is how Miss Crandall and the kindergartners and the roofer, and even Mr. Corvis felt. If they were afraid, or transfixed, or both.

The creature’s face is close enough to touch. I go to the window. Its hot, moist breath bathes my skin. Something rumbles in its throat.

“Dustin!” Mrs. Palmer screams. “Get away from the window!” She grabs me by the arm and pulls me toward the door with all her strength. But I am still, immovable, entranced by those immense red-orange eyes, terrible and final as a dying star.

Copyright © 2021 by William Jablonsky