The Secret Life

by Chris White

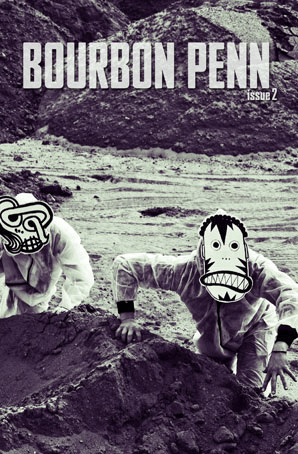

The Beach

Viv, short for Captain Alicia Viviano, was a blur for most of those two months, he remembered. Even after he retired, as he surveyed the white sands of Cuba’s coast, Major Don Marin had to work to summon her face. She had been one of what he thought of privately as “nothing people:” anonymous, busy, empty. Don often wondered whether these people found one another, perhaps led little lives that were a secret to everyone else. He’d been sure he would forget about Viv when he was on solid ground again.

An older couple passed him closer to the water and asked him how his wife was. They wore loose, linen clothes which were handsomely rumpled and had good tans. He wasn’t sure how to reply — he’d never been married — so he smiled, looking exasperated, and they gave him a knowing look and kept going. He let the exchange settle in his brain: he was close now.

A hundred yards up the beach, men in Space Corps uniforms moved around a small freighter moored near a crumbling jetty. The tide rolled along its side like a tongue. The men unloaded boxes, probably food, and stacked them in rows inside all-terrain freight trucks waiting further up the beach.

From their simple body language Don could see that they were New Men. They didn’t seem to be speaking to one another, or even interacting, beyond what was required to avoid colliding with their boxes. Don knew that once they were released from the labs, their flowers were snipped off regularly to make them appear more normal; as usual, civilians milled around them, those who knew how they were made, and searched them for a familiar face.

The Plant Room

The Defender was everything one would expect from an orbiting research vessel attended by military scientists.

The mix was dominated by greyed-out lifers, most of them enlistees, who wandered the halls and didn’t bother to salute until you kept eye contact with them for some seconds. For many, including Don and Viv, deployment on the Defender was the final assignment before retirement, so a bad review was no great threat.

Slightly more upbeat than the enlistees were the officers, to which cadre Viv and Don belonged. The Defender’s common areas were set up so that officers could maintain distance from enlistees, and vice versa, unless a complaint was to be made or someone reprimanded. The mess hall at the vessel’s hub was divided exactly in half; the barracks complex, beginning one door over, was also divided between ranks. The particulars of this layout reached Don and Viv peripherally. They lived together in the Plant Room, sleeping in separate cots in a small rest area installed therein.

The Plant Room — nickname for the Mammalobotany Lab — was located at the tip of the Defender’s Biology Wing. The facilities for the various research branches — virology, ballistics, psychiatry, among others — were arranged as spokes radiating from the central hub. The effect was that of a great bike wheel rolling across Earth’s atmosphere. The Plant Room’s many windows provided a good prospect of the surrounding space: Earth’s clouds rolled in a pleasing brown soup; the sun flared orange; and the moon, now a radioactive nugget, tumbled remedially, its pale light settling on the kidneys, the clumps of bone marrow, and the slivers of tissue that blossomed in containers on the lab’s shelves.

• • •

“What do they want us to do with this?” Viv asked.

The eight-foot steel door to the Defender’s intake bay swung away from the visiting donation vessel, which was perched like a fly on the Defender’s fuselage. A man wrapped in ice slid down its conveyor and hit the floor with a slap and a crunch. Don leaned over him and glanced at the plate that held his name, grafted into the skin of his chest.

“I reckon they’d like us to grow him,” Don said.

Viv glanced at him. “You reckon?”

“I reckon,” Don said. It was the end of their first week on the Defender. Don’s impression of Viv continued to be totally, monolithically underwhelmed. He gestured toward the man’s nameplate. “I think I knew a Tim Fairbanks in ROTC.”

A thoughtful look crossed Viv’s face. “Where did you do your ROTC?”

“Air Corps Academy,” Don said, brushing a layer of frost off Mr. Fairbanks. He was a sad sight, there in the ice. Don guessed that he’d died in a Transporter accident, or a great fall, or a blast, or something equally cataclysmic. He wondered which organs they would be able to salvage.

A live man in a navy jumpsuit and old-style baseball cap slid down the intake conveyor, holding a manifest and a folded sheet of paper. Curls of his hair reached out from under his hat. He glanced at Don and Viv, decided Don was in charge, and handed the sheet and the manifest to him.

“Present for you.” His stubble darkened in the LEDs. “Special instructions, I guess. Aren’t you folks lucky?” Don noticed that the paper was folded in half and sealed with a strip of tape — very impromptu.

“Thanks,” Don said.

Another man at the top of the intake conveyor threw the jumpsuit man a line; the jumpsuit man climbed it into the donation vessel. There was a shudder as the conveyor folded in. Some seconds later, the Defender jerked as the donation vessel detached and throttled away, its heat kissing the shell.

“You?” Don asked.

“What?” Viv asked.

“Your ROTC.”

“Oh,” Viv said. She brushed hair out of her eyes. “I enlisted. My whole family’s enlisted.”

Don glanced at her Captain’s bars.

“Explosive Ordinance Disposal,” she continued. Even after a week she was nervous. “That was my spec. I ran that race for a few years, got tired of it, applied for pre-med. I got lucky.”

Don nodded, aware that a certain kind of class rift had appeared between them. He knew she looked too old to be a Captain; judging by the lines in her face she must have been in EOD for a decade. She also had the blocky build that women sometimes get when they work with men. He didn’t press for more information. They would live together in the Plant Room for a year, after all. He glanced at her ring finger, saw that it was empty, and thought: standards can change in a year.

Don snapped the tape apart and unfolded the sheet. His eyebrows darted up, and he said, “Hmm.”

Viv waited.

He handed the sheet to her. PICK ANY SALVAGEABLE ORGAN OR TISSUE. NEW INDIVIDUAL NEEDED IN TOTAL ASAP, it said. It was handwritten and sloppy, the pen-strokes deep enough to suggest panic.

Don knew then how he recognized the man’s name. It hadn’t been from ROTC; it had been from directives, aimed at Don’s entire division, which he’d received while he was still on Earth. Don and Viv placed what was left of Lieutenant General Timothy Fairbanks on a gurney and wheeled him to the Plant Room.

“Do we have enough dirt?” Viv asked.

• • •

Before his assignment on the Defender, Don had never given much thought to what it would look like if a human being produced a fruit.

Nor had he given much thought to Planet P-225T, one of those exciting but mostly-dead “New Planets” that astronomers sometimes still discovered. It was a greyish thing, following a tight orbit around a yellow sun at the interior of the Milky Way.

A storage closet in the Plant Room was stocked with triple-layered, Kevlar-lined bags of what they called m-soil. It had been brought to earth by the freighter-load from P-225T soon after its first explorers’ feet, which had been relatively unprotected, had flowered and pollinated one another.

Don would learn that the fruit was like a huge rubbery citrus filled with blood and a strange cousin of human amniotic fluid. Once the seeds were planted, they didn’t sprout so much as simply expand into a tuber-like entity that gradually took on the dimensions and biological qualities of whatever had produced the seed originally. In his years practicing medicine, Don had never imagined that an agent would exist in the universe which bridged human and plant DNA. Left to their course in the m-soil, organs and tissues would not only duplicate, but grow into an entire copied individual. The process of reproducing a complete person took six weeks.

Sometime during Don’s second week on the Defender, his glove or his sleeve slipped while he worked: a flower sprouted on his wrist. It was tiny, white, and clustered, similar to Queen Anne’s lace. Viv anesthetized it. He learned then (he hadn’t bothered to ask before) that she was a dermatologist.

She snipped the flower off at its base. Don was unsettled to see that it had built a network of thin blood vessels in his skin, like a root system. She carved most of those out too in a large separate piece. Then, she ruined the crater with liquid nitrogen and bandaged it with several tight layers of gauze.

Don smiled at her as she studied it in the light. “Man never gave you a flower like this, I bet.” He found it a strange gesture that she kept it.

• • •

With the passage of enough time, Don would forget when he slept with Viv. It happened only once.

It was the day before the power outage, between one and two months after they began their work in the Plant Room. He understood even then that, to her, it had seemed a bigger thing than it really was.

Viv was stocky and soft and gentle, and the solar system slid over their window like an audience. Don thought it would be a nice thing, during their act, to touch her face, but he didn’t because he didn’t want her to think too much of it.

Afterward, he left the sleeping area and stood in the darkness where they kept the organs and the half-grown New Man duplicate of General Fairbanks. It seemed to peer out from within a vehicle-sized storage tank, its skin still glossy with cellulose. They’d taken his original remains to disposal as soon as his seed had sprouted. He would be full-grown within the month; they would then freeze him and load him on the donation vessel when it came by for its next drop-off. Don figured that Fairbanks would resume life as a General, though he wondered whether the m-soil had the power to mirror knowledge as it did DNA.

Don went back and slept in his own bed, even though Viv’s arm was stretched across the empty part of her mattress. She kept sleeping. He woke again some hours later; she was still asleep, but her arm was withdrawn, and that took some of the pressure off.

• • •

The power outage, one of the last noteworthy things Don remembered about his time on the Defender, was caused by a refrigerator in Earth’s orbit that struck the ship’s fuselage near the generator room, causing the generators to rattle and go offline for some minutes. The ship’s administration ran off a communication to the waste authority on Earth, who should have dismantled the machine before sending it into orbit, and hazmat checked the Defender’s generator room for radiation leaks. Don thought of home.

That day, Don ate in the mess hall and attempted to install himself into the ship’s officer community. He found them generally to be morose and superior; they would begin conversations about work, because there was little else to talk about, but would quickly tire of that, having already thought about and discussed their work to distraction. He’d left Viv alone at the intake conveyor to deal with that day’s shipment. Thankfully, the General had been the last entire person they’d been directed to grow; after him, they’d stuck to organ duplications, which were easy, and tissue duplications, which were even easier. The names labeled on the inbound body parts ran together like names on a war memorial. Don no longer paid them any attention.

When he and Viv froze the General’s duplicate for shipment back to Earth, they learned that the soil was incapable of duplicating knowledge; its specialty, and its limit, was in the hardware. It had been a surreal experience leading the General into the freezing chamber, like taking a giant child to a doctor for a shot.

“You’re Mammalobotany?” An oldish Major asked Don. Several of the officers had left the mess hall for their barracks; Don nodded and waved the conversation off.

“Help me with my prefixes and suffixes, will you?” The Major continued. “Plants and animals?”

“That’s right,” Don said. He detected a shade of resentment from the old Major.

“And the lady you work with; you get along?”

Don looked at him.

The Major shifted in his seat and licked his lips. “There’s something I’ve been wondering about her.”

“What?”

“Is she a lesbian?”

“No.”

“You asked her?”

Don felt the trap close. He stayed silent too long; a smile blossomed in the Major’s face.

“Send her over, yeah? Unless you two are serious. You know how many women are in ballistics?”

Don returned to the Plant Room without saying anything. Had that been a joke? He wasn’t sure.

• • •

He found Viv in the Plant Room, surrounded by the organs, hunched over a single container. She didn’t look up when he came in, which was fine. Don went into the kitchen area and brewed himself a single cup of coffee. The smell filled the lab, close and dark and bitter.

“How hard do you think it would be to grow something in secret?” she asked after a time. Don sipped.

“Who knows,” he said, looking at the window.

She looked at him for a long time, which he didn’t like.

• • •

The next week, the Defender’s administration reassigned Viv to a reconstruction detail on the coast of Cuba, where the fighting was winding down.

Don checked the organs that came up for her name when he could remember to do so.

The Beach

The war continued long after Don left the Defender and retired. It ceased to be his concern.

The last contact he’d had with any military personnel was a communication he’d received at his home in Los Angeles, from a former CO, asking him what in the world he hoped to accomplish shacking up in a war zone like Cuba.

He read the letter three times. He’d never been to Cuba.

He tracked Viv as far as Holguin.

Don touched the scar on his wrist. He wondered how it could have been for her, having a blank-slate version of Don to which she could say and teach anything. Two nothing people finding one another, he supposed.

He followed the linen-wearing older couple past the regiment of New Men and waited for them to make eye contact with him before he spoke.

He told them that he needed to call Viv, but he didn’t have her number memorized (it was saved in his phone, which was at home, but he never looked at it; why should he?). The sea rolled up and surprised them. Don thought he should laugh. But the laugh must have been wrong, because the couple’s eyes darkened, the tiniest shade, with suspicion, or fear. It was awkward when they refused to give him Viv’s number. After they parted ways, Don watched from the sidewalk some distance away as the couple approached the sergeant overseeing the unloading, probably to inform him that one of his New Men had escaped and was searching out a civilian.

Copyright © 2011 by Chris White