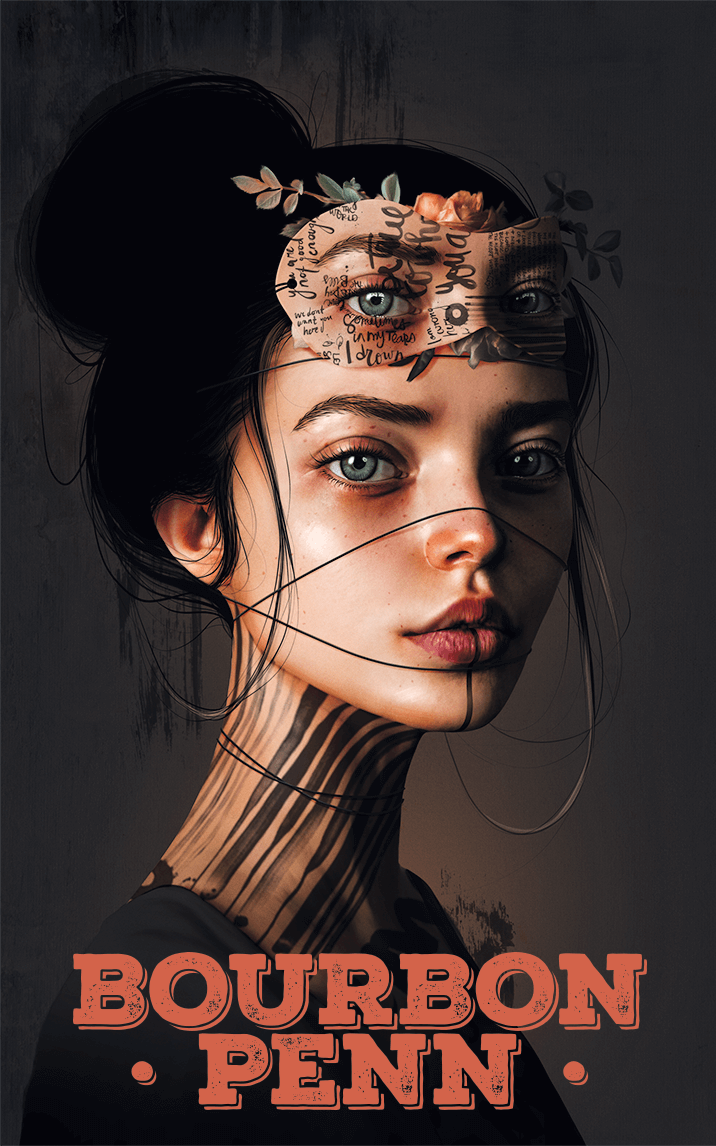

Joshua Told the Children to Shout

by Amanda Baldeneaux

‘S’ is a magic letter because, like God, it multiplies. Hurricanes also multiply. They are like God, so they also get names. Hurricanes are a pantheon of deities sweeping the south and the eastern seaboard with wrath, wiping clean the slate like the city of Jericho when the walls fell down; no man, woman, or child spared in their wakes. A week ago, we prayed to Hurricane Sloane to spare us. She did, almost. Davensport avoided the direct hit predicted and instead enjoyed a strong sideswipe of Sloane’s tail, whereas our neighboring town, Gulf Shoals, took the direct hit in our place. Their walls fell down.

Hurricane Sloane multiplied whole houses into hundreds – thousands – of shrunken, splintered structures. Some will never be rebuilt. God warned against anyone who dared rebuild the original walls of Jericho, and here in Alabama we know better than to tempt a hurricane with a duplicate of a structure its brethren have already destroyed. Whatever the hurricanes take are theirs, forever. But hurricanes also give, too. That’s how the body floated into my basement.

‘S’ is a magic letter because it bestows possession. The ‘S’ giveth and the ‘S’ taketh away.

Sloan took away plenty. Not the hurricane, Sloane. I mean Sloan, Clayton’s new wife. She took him. Sloan’s husband. Sloane’s beach house. The hurricane’s, not the wife’s. Hurricane Sloane devoured our – Clayton’s – house in Gulf Shoals with him and the new wife inside it. Presumably. Gulf Shoals wasn’t supposed to be hit. A light grazing, only. He’d gone to board it up, his mother told me. She keeps calling, asking about the ring. My ring. Shanna’s ring. The ‘S’ giveth. The ‘S’ keepeth.

I always thought ‘S’ was magic because it started my name. A snake of a letter, winding itself round dead space in shapely curves. My husband – when Clayton was my husband – said the name ‘Shanna’ sounded like mist, like something a waterfall would say if you listened to it from far enough away that the roar reduced to a whisper. A dispersal. That’s what my mother said happens when you die. She’s agnostic, a truth she could never say out loud when she taught at the St. Margaret Catholic School for Girls. Now, she says whatever she wants. It’s disturbing.

Disturbing. Dispersal. Disappearance. Death. All the worst words start with ‘D.’ Displaced. I suppose ‘S’ has its moments, too. It does lead both parts of ‘storm surge.’ Sin. Scandal. Then again, ‘drown’ starts with ‘D.’ Dalliance. Delusional. Divorce. But I digress.

The storm season began early this year. Sloane came on schedule. September. It was my first summer alone. A divorcee. It was the summer of miller moths flying through my halls like ghosts in a haunted house. They were everywhere. Clayton was everywhere, still. The moths flew to the lights on the porch and stayed till they died. They swept in with the open glass slider to thwack against the kitchen light in rhythmic thumps that burned their wings to a useless crisp. I scooped them everywhere, found them drowned in the dishwater and bathtub, into my cupped palm and into the trash. They crawled beneath the crack between the bedroom window screen and where it’d torn back from its track. They clung to siding. Garages. Spiderwebs. Clogged swimming pool filters. And when the air turned cooler and they should have all been dead, the thwacks against the lightbulbs continued, even though the moths themselves were gone. I had no explanation for this, but what woman alone can explain every bump in the night? Then, the cicadas started.

I’d never liked insects. I’d crunched enough June bugs beneath my bare feet by the time I was twelve to be happy if I never saw an insect again. Their outer wings littered our back porch like spent nutshells. I didn’t like moths better, even though they could fly. They were always turning up dead along the baseboards of our house. My house. The husks of their bodies turned to dust with the brush of a fingertip and seemed to explode into the stuff in the vacuum. What was even the point? Maybe if my mother had been religious, I’d feel different. Dust to dust. Ashes to ashes. There’s a reason the Bible doesn’t talk about what happens to a body when it drowns; no one wants to think about bloated goo. The skin dissolving to the touch after floating face down too long. Mold to mold. That’s how I’d found the rabbits that used to live in the yard when the waters receded: face down and surrounded by sticks; mold blooming like flowers behind their ears.

The body in my basement must have come through the smashed glass sliders that led to the patio off the downstairs rec room. It washed in with two feet of mud and raw sewage, judging by the smell and the way none of my toilets wanted to work since the storm wall passed. The first time I flushed sent everything I wanted gone back up into the pan of my master bath shower. Women weren’t supposed to need to deal with things; it’s why we get married. Clayton violated that – his usefulness – along with our vows. He’d violated our divorce settlement, too, when the check didn’t come after the hurricane hit. That’s why I’m down here now, knee deep in shit with a shovel in hand, mucking out my carpeted basement like a horse stall. The water out back has receded down to the fence line, but Gerald – the only neighbor who stayed – tells me not to count on it being gone for good. Two steps forward two steps back, he says. That’s how hurricanes go. It hasn’t stopped raining in days, and I can already see that he’s right, the water snaking back between the wrought iron fence posts into the yard. Spots of mold are starting to climb my wallpaper as though the rose vines printed on it were an actual trellis. If Clayton is alive, I need him to get off his wife in the bed in the beach house we’d picked out together and write me a check before the rot reaches inside the walls and chews through the studs.

They don’t think he’s alive. His lawyers have already phoned me about the will. I told them to review it again, as my name was not in it. I have demanded an appeal. Demanded. Demeaned. Demoted. Demon.

I try not to think thoughts like that about his new wife. They do not become me, though at this moment I am not myself at all. I have company.

After inviting itself in, the body bumped against the sectional sofa and parked itself behind Clayton’s end-piece recliner. The body is the same build as him. I see tufts of mud-crusted blonde hair, just like his. The body is face down and frosted in splotches of mud, but it might be him. I have squinted at it six ways since Sunday, and I believe it could be Clayton, come back for me.

I’ve dialed the coroner but have been on hold twenty minutes. I scratch at the name I’d written on my arm in permanent marker, my skin pink from displeasure at the ink and the wet and my nails. It chafes. I could have evacuated to the arena three hours north, but I couldn’t have my face filing inside on TV with the rest. What would everyone think? There goes a fallen woman: since her husband left, she has nowhere to go.

• • •

A living human answers the phone as I come round to the front of the house for some air. Gerald is riding the block in his golf cart with his gun in his hand again. Since the evacuation order, our attendant at the neighborhood gate has been absent, and Gerald has taken matters onto himself to prevent vandals from looting the homes left behind. He waves.

“A body,” I say into the phone. “A drowned man. Yes. In my basement. No, I don’t know how he got there. The slider is broken. You need to ID him. I think it’s…”

She puts me on hold again.

“Everything alright?” Gerald parks the cart by my front walk, the electric motor’s hum cutting out.

I point to the phone at my ear and turn my back. I don’t need Gerald McClune knowing my house has become a repository for the recently dead, even if it is my ex-husband. It might be my ex-husband. I’ve considered flipping him; dragging him up the stairs to our room if it’s him. But the mud on the carpet, the dead weight.

It doesn’t help that half the neighborhood had put up their October decorations early: skulls and spiderwebs hanging from every tree. A fake graveyard survived the flood and still sits staring at me from the water-logged lawn of the Anderson’s home across the street. They have three children at St. Margaret’s, nice family. I don’t need them or anyone else looking at my house like it’s an actual morgue. And what if I have to sell? I don’t want to disclose this. I consider hanging up.

“Yes, I’m still here,” I say, when the woman comes back. “You want me to what?” The front porch lights flicker as she repeats herself. The power has been spotty ever since the storm, but at least I can normally charge my phone. The lights go out. My phone battery is already down to less than twenty percent. “Shit,” I say, the woman still on the line, and hang up before she can write down my name and address.

“You’re a brave woman,” Gerald says. “In so many ways.”

I don’t like the way he says it – the way he’s been saying it since Clayton left, and before that. Since what happened to Simon.

‘Pity’ is a word that sounds like pit. I won’t sink into anyone’s pit. Not even my own. I regrip my shovel, wondering if I’d be strong enough to drag Gerald down to the flooded golf course after a good thwack to the head. He stayed behind in an evacuation zone. Who would ask questions if he washed up dead?

“I don’t abandon my home to the wolves,” I say.

“I admire that, Mrs. Turnberry. Power out again?” Gerald’s eyes wander up and down my body and I tug the long, light cardigan that drapes loosely across my chest.

I nod. “It comes and goes.”

“They got the linemen coming in from other states. I’m going to make a call to get them out this way first. Can’t have the lights off in an empty home. Invites trouble.” Gerald hiked his pants up his waist. “You sure you’re alright in there by yourself?”

I consider telling him I’m not by myself but think better of it. “I’ve survived this long,” I say. “Families have been checking in with me each day. I tell them what good work you’re doing, with your patrols.” These are lies. No one has called to check on me, or their homes. They check in with their security companies. Their insurance claim filers. Inspectors. I’ve seen the cars coming out one by one. Parking. Snapping pictures. Homes up the hillside are fine, mostly. It’s those of us on the golf course side, downslope, with the water and sewage and mud. I wonder if any other houses have bodies. I wonder again if it’s Clayton; if he’d tried to come home. I do and do not want to check. It should be him; he owes me that much – to come back.

I return to the basement and consider the body. The coroner’s secretary told me to put mud over it to keep him fresh till they can get someone out there. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised that there’s a run on the coroner’s services. I debate once again rolling him over to check the face, but it’s dark as the sun sets and I don’t like being down here with a dead man, Clayton or not. Especially if not. I shovel a few scoopfuls of mud over the back of his head like he were carrots being put up for the winter. I am concerned about the scent of death wafting upstairs to my kitchen, but perhaps that would be nicer than the smell of overwrought sewage plant that no number of Yankee Candles has been able to cover, though I will keep trying.

I peel Clayton’s trout fishing waders – one of the few things he left – down to my ankles, leaving them draped over the banister behind the basement door. The sun sets in front of the house and the kitchen is dark without power. I take a candle off the windowsill – Christmas scent, far too early, but it’ll have to do – and trim the black wick down to a stub before lighting. The wick leaves a black streak on my index finger and thumb before I drop it into a glass bowl I keep by the sink to empty later. The black trimmings have streaked the bowl like tally marks scrawled into the wall of a jail cell. They accurately measure how many days since Sloane slammed our whole coast.

My phone rings and I answer quickly: I can’t have my battery die and then wake up to vandals and looters carrying my flat screen out my garage. Or worse.

“Talk fast,” I say, instead of hello. “No power.”

The contractor I’d asked for a quote to repair the damage done to my roof, walls, and who knows what else reads me a list of recommended repairs and a total.

“That’s too much,” I say. “I can’t do that right now.” I’m not sure I can even buy milk for my coffee right now.

“If you’ve got water damage in your walls, like I suspect, the whole structure could be compromised,” he says.

“A few missing shingles do not mean my house is going to collapse,” I reply. “This house has survived six hurricanes since I’ve lived here, and a little mud in the basement is nothing a steam vac can’t handle. I’ll get a quote elsewhere.” I hang up the phone, my blood pressure rising. There is no quote I can pay to patch up my house, not until Clayton rises from the presumed dead and sends me the alimony that I am owed. I consider the body in my basement. I don’t like the idea of a dead man floating beneath my feet, but I’ve slept over plenty of dead things before: raccoons beneath the front porch. A cat trapped in the crawl space beneath the foundation. Why should it start bothering me, now? Dead litter the beaches, first responders digging them out beneath swollen wood and overturned boats. Why should it matter if they are beside me, above me, or below?

I open a window to air out the kitchen from the basement’s foul smell, but the flood on the golf course doesn’t smell any better. I leave it open, anyway. Cicadas in the pine trees surrounding my house begin to call out to each other in shrill screams. Maybe it’s the quiet of the deserted neighborhood, but they seem louder this year. More numerous. As though each tree held a whole colony of cicadas vying to out-screech each other from every limb. The last time I heard them this loud had been … I shake my head. I don’t want to think about him.

Seventeen years ago. That’s how old he’d be. I was acutely aware of his birthday, this year, as the ocean gave me Sloane to remind me. I move the candle to the table and curse. A crack has formed in the tiled backsplash beside the sink.

The lights flicker back on and the air conditioner hums back to life. I close the windows just as a loud crack, like lobster shells splitting, sounds out from the basement. I throw open the basement door.

“Hello?” I call, thinking the body has just sprung back to life. No one answers. I close the door again, gently. Consider blocking it with a chair. If he’s alive, he can let himself out the back through the plywood; it wouldn’t take much muscle to move it. I could only find a few nails. I check out the window for wind; a cause for a tree branch to thwack the side of the house or snap off its trunk. The air is still, disturbed only by the deafening shriek of waking cicadas and the soft flutters of moth wings, the survivors banging into the glass of my porch light. I have work in the morning and can’t oversleep. I clutch my phone and carry it upstairs to plug in., lest my alarm’s power source not survive until morning.

• • •

I have been substitute teaching at St. Margaret’s School since Clayton left. It is no longer just for girls, as when my mother worked there. She used to take me to work with her, on days when I was too sick to go to my school. The public school. I remember her students, their plaid skirts and bare knees, their hair molded into smooth bobs with hairspray and lacquered barrettes. They wore crosses and gold lockets and pearls around their long necks, already looking like the little wives they’d become. My mother taught them science. I hid behind the wooden ship of her desk and peeked out at the girls of Davensport who were destined to marry the town’s doctors. Bankers. Lawyers. The girls who would treat college like finishing school and would forever have money to spend on extravagances like jackets that weren’t meant to keep you warm and gold foil ribbon at Christmas and lipsticks in seasonal shades. I wanted to send my own child here, but he never came.

I’ve been filling in since most of the teachers went north. The principal, Father Elijah, asked me to stop by his office before my first class and I am hopeful that I’ll be offered a more permanent position to better secure my financial future. Clayton had the retirement accounts. The stock. The liquid assets.

A crucifix hangs over the window behind Father Elijah’s desk, just as it had done when my mother was a teacher. I sit in the chair, still made uncomfortable by the likeness of a dead man hanging above me, more uncomfortable, perhaps, than I was last night with a dead man sleeping beneath me. Not that I slept well. With the windows open, I was sure I heard whispers from downstairs; vandals come to break into our homes. I could not relax. I can rarely relax. I’d have made a good Catholic, in that way.

Clayton was Catholic. I am not. On our crosses, the dead man has already risen and gone about his day. I had considered converting for Clayton but decided I preferred the empty cross – the reminder of resurrection, of the dead rising – since.

Father Elijah closes the door, adjusts his black robes, and sits down. It’s cold in his office with the air conditioner blowing. In this state, there is no such thing as room temperature. The humidity means you are always chilled from the damp or feverishly warm. I wag my foot to ward off goose pimples beneath my stack of gold bracelets as the priest explains that busloads of families have been brought into Davensport from Gulf Shoals to sleep in community centers. Further, St. Margaret’s will be hosting some of the displaced students.

“You’ll take a history-English block for sophomores and juniors in a building outside,” he says.

“A portable?”

“We have to save space for when our students come back,” he says. “We don’t want to displace our tuition-paying families. You understand.”

I did; money always came first. “These students,” I ask. “Are they…?”

“From public schools,” he says. “There’s more than the school district can take so the private community is stepping in. There’s no doubt, after what these children have been through, they could benefit from our help.” He eyed the Bible standing upright on the corner of his desk. He slid a folder with crossword puzzles across his desk. “Just get to know them, today.”

I do not want the folder or the students. But on paper, I’m as poor as they probably are, with just as many choices.

• • •

The portable is on the other side of the tennis courts, one of several used for storage, the desks still stacked to the ceiling along the back wall when I enter. I barely have time to write my name on the whiteboard before the students file in. They do not wear uniforms. They smell like pleather bus seats and sweat. The girls wear liner so thick on their eyes they appear nocturnal, like animals peeled out of their dens into daylight. Only several have backpacks, I’m not sure all of them have even a pencil. They loiter along the back wall and whisper.

“Don’t just stand there,” I say. “Get a desk and a chair.” I motion at the stacks of furniture. If I’m lucky, organizing them into rows will take most of the morning. I scan the roster and freeze on the name ‘Simon.’ My son’s name. I glance at the students, attempting to discern which child got to live on with the name, when my child did not. He’d have been their age, my Simon. Seventeen.

The whispers get louder as the desks clatter off each other and into crooked rows on the floor. I stand with my arms crossed, waiting. “Rich bitch” is bandied about. If only.

“Is there a bathroom?” a student asks.

“It’s hot,” another says. “Where’s the AC?”

They lean back in their chairs, bored before any lesson has even begun. By lunch, I am certain most of them have never actually been to a school before and were brought here because the juvenile detention center must have flooded as well. I knock on Father Elijah’s office to tell him. The man smiles.

“They’ve been displaced from their homes,” he says. “They’re upset.”

“Give them a counselor,” I say. “They aren’t here to learn.”

“They’re not our usual students,” he says. “But they’re still children.” He laces his hands across his stomach. “On the seventh day the Israelites marched around the walls of Jericho, and the priests blew horns, and the Israelites shouted, and the walls of the city fell, and the city was taken for God.” He swivels his chair, the screws squealing. “Children make noise and shout, but it’s to bring down their own walls as they grow. Understand?”

I cross my arms.

“Our job is to help guide them through times of trial. I know it might not be easy, but I’m sure that once our students return, we can find a permanent place for you. If you can handle this bunch, you can handle anything.” He winks at me before standing.

I had already been through times of trial. Losing Simon. My husband. Fighting for every penny of alimony. Surviving a hurricane on my own.

The linemen and the tree trimmers would be arriving shortly. As soon as the power was on, the tree branches removed, and the water pumped out of the trailers and backwoods where these children came from, they could go home. How long could that take – one week? Two? Keeping them busy can’t be too difficult. They mill around the parking lot at lunch, sitting on car hoods that aren’t theirs, unscrewing antennas to swat each other as though the metal poles were switches. They lean back in their chairs in the afternoon, chins tilted toward the ceiling, thumbs busy on cellphones. After school they are back in the parking lot again, drifting from one side to another like flotsam trapped in eddies. They stare at each teacher as we walk to our cars, including me, and I do not like it at all. The one I have learned is named Simon snickers as I unlock my Mercedes, and it irritates me to not know what he finds so amusing, and it concerns me that they can see what I drive, which direction I point it as I pull out of the faculty lot. I worry they’ll follow me, like lost dogs looking for food. Like ghosts caught up in water. I glance in my rear view on the main road, but it’s empty, save for dragonflies hunting over flooded canals.

• • •

Home from work, my front door creaks as I push it open, the bolts rusting in their hinges. The water is pervasive. This morning, water beaded out of my earlobes when I pushed a diamond stud through the hole, wetting my fingertip. The condensation in the master bath never dries, the mirror permanently fogged. I am lucky the water heater in the house is gas. The stove. The furnace. At least I can cook and bathe even when the power goes out, but no amount of bathing seems to get out the smell of the flood waters downstairs. A roach scurries across the siding and behind a bush as I go inside. I shudder, stifling a scream. I don’t want Gerald to come running. I hate roaches. I wonder if the dead body is attracting them. I go into the kitchen, debating whether to call the coroner or the exterminator first. I’ve left three messages with the exterminator since the bugs began taking over. They used to spray every month. I have no problem with poison perimeters. I prefer them.

I set my purse in the foyer and see the footprint on the floor, a faint outline of mud. I have been careful not to walk with my shoes in the house and do not understand how I could have been so careless as to tromp mud across the marble tile without notice. The rest of my shoes sit neatly in a boot tray on the floor of the coat closet. I scan the living room for broken glass.

“Hello?” I call out. “I’m home and I’m armed.” I hold still, hoping vandals in the house will scramble out a window if they’re here.

The house is silent. I press my foot to the print, comparing sizes, to see if it is mine but already, I know my shoes do not have that heavy a tread. I roll my eyes at myself; I don’t have time to be scared. The mailbox had utility bills and my credit card will start garnering interest that will balloon beyond capture. I move to the kitchen to make myself toast before addressing the bills or the body downstairs.

A juice glass sits on the counter beside the sink. I thought I had loaded the washer with every last dirty item this morning. I open it and am hit by a wall of hot steam. It’s clean. I set the used glass in the sink and dial the coroner. Get voicemail. The crack in the tile is longer now, snaking up behind the cabinets. A new one has formed by the door that goes onto the deck. I open the windows to air out the damp and am hit with the stench of the standing water out back.

When Clayton was here, we’d have wine when he got home from work. I’d make dinner and he’d watch the news in the keeping room just off the kitchen. He preferred it to the living room. Smaller. Quieter. It shouldn’t surprise me that his new wife, Sloan, matched those descriptions, too. I’d hoped he grow tired of her, a woman blown around easily as dead leaves. I wet a kitchen cloth with warm water and pull on the fishing waders over my hose.

There is a broken board beneath the seventh step down and my boot nearly goes through. Clayton had said he would fix it. He used to like fixing things: leaky faucets. Unlevel tables. Broken antiques. I knew something was wrong when he stopped taking on projects. He stayed late at work, was always on call. He didn’t notice when I wore my silk robe with the slits up each leg. I thought he’d been shaken by the news of the murder three cul de sacs over. Crime didn’t happen in this community; the walls were high, the gate always manned, and people who lived here didn’t like to make scenes. Then the Seibert kid turned up dead in his yard. He’d been seventeen. Dealing drugs, we found out, probably owed somebody money or made promises to people he shouldn’t. What did he need the money for? His parents drove Teslas and vacationed in Cabo. I wouldn’t be surprised if some of the kids from Gulf Shoals in my class today had been customers. Or shot him. What good were the neighborhood walls, then? What good are they now, with floodwater washing out the mulch in our perennial beds? Anyone could kayak on in and set up a squatter’s house till the families come home. If the families come home.

The body in the basement has floated around the sofa and bumped against the wall beneath the flat screen TV. There must be a current in here, which means more water coming in. It’s certainly not flowing out. I steel myself and wade to the body. I’ve decided I need to see his face. I need to know. I have worn my pink rubber dish gloves – my last clean pair – and grip the man’s shoulder. I flip him. I close my eyes, scared of what the water might have done to his face, but I have to look. I open each eye one at a time, then wipe away the mud from his cheek.

It’s not Clayton. The face is too young, the skin too smooth. Early twenties or teens. He could be Clayton’s senior photo, and I am unnerved. It is difficult to tell much distinction through the sagging lips and mouth full of brown water. A roach thrashes on its back by his hand. My lunch of red lettuce leaves and wrinkled tomatoes rises up my throat and I run up the stairs, ready to heave into the porcelain sink. The air helps it pass and I call the coroner’s office again. They tell me three days and they’ll be here. To just leave it alone until then. A moth thwacks the bulb in a pendant light over the island. I vow not to go back downstairs to the dead stranger again.

• • •

Clayton’s mother calls as I am sitting on the edge of my bed, ready for sleep. I’d tried taking a shower but kept picturing muddy hands snaking out of the open drain when I rinsed, so I had to get out. I have never liked living alone. Sleeping alone. I don’t like the thought of dying alone, either. It is early for bed, but I’m not one for TV and I just want the next week to be over.

“I’m calling about the ring,” Wendy says.

I twist the ring on my finger. “What about it?”

“It was my mother’s,” she says. “I’d like it returned.”

“Clayton gave it to me,” I say. We’ve had this conversation before.

“We’re planning a service,” Wendy says.

“Have they found the body?” The lamp flickers and the electricity dies. “I have to go,” I say. “Power out.” I hang up before she can reply, and a crack sounds from downstairs. I startle, thinking a support beam has fractured, but loud rapping sounds in the foyer. I slip on a robe to go see if it’s the coroner or Gerald or worse. The lights flicker on.

Through the glass inlay I see three faces distorted by the beveling and shadows. I open the door and three teenagers from my portable classroom blink back at me.

“Evening, Ms. Turnberry,” they say, more cordial than they’d been in their desks. “Need anyone to mow your lawn? Muck a basement? We’re looking for jobs.”

It is difficult to hear them over the screech of cicadas, and they blink like owls as I piece together what they said over the swarms of the insects in trees. I shake my head. “Have you applied at McDonald’s?”

“They won’t hire us,” Simon says. “Don’t know how long we’ll be here.”

I want to ask him where his name came from, if his middle name is Mark, like my son’s, but I don’t.

“Did you know that I lived here?” I asked, considering the strange footprint I’d scrubbed, and the juice glass left out by the sink. “Did you follow me?”

The three shake their heads. “We’ve gone door to door.”

“This neighborhood is empty,” I say, then regret it. “The families are coming home tomorrow.”

“Your lawn?” another asks. “We need to earn money.”

“I don’t have much money,” I say. “I work at a school.”

“This is a nice house.”

“It was my husband’s house.”

“Where he at?”

“He’s dead,” I say, and know it is true.

“You got a ring,” one says, pointing to my hand. I hide it beneath the other.

“A woman can grieve,” I say. “I don’t have anything to give you. Run along, before the neighborhood patrol sees you. Soliciting isn’t allowed here.”

“The gate was open,” Simon says. “No one stopped us.”

“We’re all trying our best.” I close the door and bolt it. I close the windows with sensors, despite the trapped stink of the sewers, and arm the alarm before going to sleep, praying the power won’t go out again.

• • •

My home alarm beeps once in the night, waking me. I fall back asleep when it doesn’t go off again. A fluke. A moth.

The next morning, garage doors are graffitied. I’ve no doubt it was those boys, and I’m sure the tagging will continue until the families return. I check my own house, but it’s clean. Gerald’s house has the area code for Gulf Shoals on the fence.

At school, I corner the boys before lunch by the door.

“There’s graffiti in my neighborhood,” I say. “It wasn’t there before dark.”

“I don’t know anything about that,” Simon says. “We left after we talked to you.”

“My security alarm went off,” I say. “Did you come back to my house?”

Another boy shakes his head. “We knocked on a few more doors before leaving. There was someone outside in your yard. You got a son?”

The question feels like an attack. “Go to lunch,” I say.

“We can protect your house,” Simon says. “We charge by the hour.”

“I don’t need protection,” I say. “This is Davensport. This is civilized society.”

• • •

At home after school, I realize I have been broken into. The back door to the deck hinges open and bugs have flown in, swarming a bowl of warm milk left by the sink with a spoon sticking out. I didn’t eat cereal this morning. I rarely eat it at all. The only boxes left had been Clayton’s, stale in their plastic bags.

I walk the house, checking my jewelry drawer. The laptops and printer in the office. My files. Nothing is missing beyond the portion of cereal.

I crack open the basement to peek down the stairs and realize the water has risen at least two feet since last night, and the body has floated into the stairwell. Its head bumps against the handrail, as though trying to come up the stairs. I slam the door shut. Shrieks sound from outside and I run to the window and see kids riding by on bikes. They do not belong to this neighborhood, but the bicycles do. I look in my garage, but I have nothing of interest to children, except cereal, which they seem to have taken. I am shaking, angry that they’ve been in my house and the water is rising.

I set the used bowl in the sink. I should buy caulk for the crack. The cracks are multiplying. I’ve seen another in the hall by the stairs. I open the dishwasher, the steam swelling small beads of sweat on my face. I take out a stack of plates and carry them across the room when the screams sound again and I startle, dropping them all at my feet. They shatter in a wide circle around me. I stand in the center of broken white glass, barefoot and stranded.

• • •

I sit on the edge of the bed picking glass shards out of my skin with my tweezers. I twist the ring on my finger, working it off. Simon used to like me to do that. He’d try the big diamond on his pinkie for size.

There is a glass shard beneath where the band had sat. I will need new plates. Matching bowls. I set the ring on my nightstand and arm the alarm, hoping the electricity holds.

• • •

It’s the cracking that wakes me up, like a bat splitting a baseball in half. Suctioning squishes, like boots stuck in mud. Thumps sound up the stairs. I sit up, heart hammering louder than the steps I hear coming up, when they stop. I question whether to shout out a warning or hide, when a whisper seeps down through the air vent overhead, as though the HVAC had learned to shape air into words. I cannot deny the sound of the word, the clarity with which it is spoken – voicelessly, breathlessly: “Mom.”

I press ‘panic’ on my alarm and the house rings out in shrill shrieks, drowning the sound of cicadas out for the first time in weeks.

• • •

The police arrive in an hour. I tell them about the boy in the basement. They look, shining flashlights across the black water.

“We don’t see him,” they say. “Are you sure?”

“If you don’t see him, he sunk,” I reply. “He’s been there for days.”

“Is anything else missing?”

I shake my head. “Someone came in while I was at work,” I say. “They ate cereal.”

“Sounds like kids.” The officer jots something down.

“They broke into the neighborhood,” I say. “They spray painted the homes.”

“That’s not uncommon,” he says. “They’ll be gone soon enough.”

“What about now?”

The officer shrugs. “Nothing’s missing.”

“The body is missing.”

“We’ll come back tomorrow,” he said. “Dredge it up if it’s there.”

“It’s there.”

They leave and I go back to bed but can’t sleep. The cicadas are screaming, but I can’t close the window. If the windows are open, I’m not trapped inside, with whoever is here. Whatever is here. Tomorrow is Saturday. No school. I leave on the lamp on the nightstand and that’s when I notice: my wedding ring, gone.

• • •

Clayton’s lawyer calls the next morning.

“We’ve reviewed the will,” he says. “There’s no changes.”

“What do you mean?” I ask. “He can’t leave me nothing.”

“He can,” the lawyer says. “This will is outdated, but it leaves everything that he had to a son. As the son is deceased, along with his wife, all personal property reverts to his next living family. His parents.”

“That was our son,” I say.

“I’m sorry,” he says, before hanging up.

I stare at the phone, the screen black as the water downstairs. Simon died at three, bit by a snake in the bushes out back. Bushes I had cleared since. Clayton had been at work when it happened. I’d heard Simon scream, but he screamed all the time: spiders. Cockroaches. He didn’t like bugs, lizards. He didn’t like to get dirty. I don’t know why he was under the bush in the mud; he had a perfect new swing set standing unused in the grass. For years I could still hear his screaming, the shrill screech of his terror bouncing off the limb of every tree. I slept with pillows over my head. I slept with the windows and doors boarded up. He’d have turned seventeen the day Sloane barreled in.

• • •

The exterminator arrives unannounced the next morning. I find him walking the perimeter with his tank of poison strapped to his back. He is spraying the wet siding and dirt. I run after him as he climbs the steps up the deck. I point to the trees.

“What can you do about them?” I ask. “The cicadas.”

He smiles. “They’ll be gone soon enough.”

“I can’t sleep until then.”

“They’re worse this year because the periodical nymphs are coming out of the ground.”

I blink at him.

“Some cicadas only come out after seventeen years underground,” he says. “When they come out, it’s a party. Twice as many as usual, if not more. They’ll mate and get eaten. Go back underground.” he said. “Then, quiet again. This doesn’t look good.” He shakes the handrail of the deck. Wet pieces of wood splinter off.

“The whole house is flooded,” I say.

“I’d stay off this until it’s shored up,” he says, shaking it harder. The nails creak and the wooden beams crack. He jogs down the steps and keeps spraying.

• • •

The electricity goes out before dinner. I reach for a candle and trim the wick. I drop it into the bowl by the sink, but the rest of my wick trimmings are gone. Did I wash the bowl? The black streaks are gone, a countdown wiped clean. I carry the candle upstairs.

Kids scream outside and I startle, checking out the window for Gulf Shoals delinquents to ride by on stolen bikes. I wonder if they’re living here, inside the houses. I wonder if they’re living in mine. I go to lock the bedroom door when a scream comes from inside. I run to hit panic but without power, the alarms can’t be synced. The screaming gets louder, and I’ve had enough. I throw open the door and march down the stairs, ready to bludgeon whatever little thief that I find.

I follow the sound and realize the screaming comes from inside the basement. The kids who broke in have found the body, I assume, and I smile because it serves them right to be scared.

As I cross over the kitchen, the tile floor is slick with a thin layer of black water. The screaming stops. Determined to catch them before they can swim out into the yard, I throw open the door to the basement and march down the steps. I hold up the candle, taking in the couch, the upholstery ruined. The TV, an electrocution waiting to happen. The wet bar and its upside-down polished wine cups, still hanging pristine above all the muck. The plywood over the slider is there, mold-covered but whole. The basement door slams shut behind me.

“Hello?” I shout up. I wade back across the silt that used to be carpet, calling, “Hello? Hello?”

The sound of studs in the walls and the ceiling cracking are all I hear answer. Then, a scream on the other side of the door. The body in the basement is missing. I fight the mud and the cold to wade to the stairs, and in the candlelight, see two sets of footsteps on the carpet: my own, bare toe prints molded into the squished, soggy fabric, and the other: mud-caked and large, going up to the house. Muck-crusted handprints are dragged on the drywall. I want to scream, but the house is already full with the shrieking, a swarm on the other side of the door, screaming their presence after seventeen years in the ground.

The walls shift under the weight of their volume, the frame of my house sagging its way out to sea. The foundation will be shorn bald by morning if the children keep screaming. If my Simon keeps screaming. I’ll wash clean away with the house. The roof lowers to meet me as I climb up the stairs, splinters snapping out of the wall.

“Simon?” I call. “Simon, did you come home?”

The screaming continues and I realize I have been all wrong about the letter ‘S.’ It is not the most magical letter. It is screaming. It is sinking. It is separation and sadness and sleepless. It is a little boy, scared.

Copyright © 2022 by Amanda Baldeneaux