Fat Kids

by Alex Jennings

Sometimes when I sleep, I wander too far from my body—or at least that’s how it feels. It’s like swimming out to sea, being caught by an undertow and knowing you’ve gone too far to make your way back to shore. Except I always do. It got worse during the Pandemic. My girlfriend taught in-person classes at Lusher, but I’d worked exclusively at home for years. Never having to be anywhere in the morning meant going back to bed as soon as I was done walking the dog and waking up at just any old time unless somebody needed something.

The first call I got that morning was my agent telling me that the manuscript for my first novel had been accepted for publication. I sat in my scratched-up red leather wingback in my bedroom office feeling full-body chills. So this was real now. I’d worked toward this moment for the last ten years—more—and here it was. I sighed.

“Thanks, Shawna,” I said. “That’s—that’s a lot.”

“How do you feel?” she said.

Still groggy and disconnected, I thought. “Good. I feel—”

I bit off the words as I saw another call incoming, this time, from my girlfriend Saadiqah. She had bad news about the hurricane in the Gulf.

“What’s it doing?” I asked. The conversation was far from unusual. This happened most every year. A storm would enter the Gulf of Mexico, gather strength, and we’d play chicken with it, hoping it would veer away from New Orleans before we had to evacuate. You could say this mostly annual calculation was like the Sword of Damocles, but it wasn’t that dramatic. It’s just the sort of thing one got used to living here.

Diqah’s voice dropped. “They say it’s a four now.”

“No shit?” I said. “Cat 4?”

My own personal rule had always been that we’d bug out for anything above a Category 2, but Diqah’s beat-up Corolla wouldn’t get us far, and rental cars were in short supply.

“What should we do?”

I shrugged. “Hit up Walmart like a couple of fat kids and get a good room up the street.”

• • •

Many of the hotels in the Central Business District had generators, and even if the power went out in our apartment, it would likely stay on at the Loew’s. So we raided the Tchoupitoulas Walmart for hurricane snacks, bundled up our dog Karate Valentino, and called a car.

The only hurricane I’d stuck around for was Isaac in 2012. Just me, my girlfriend at the time, and her cat. The only thing that truly frightened me was the sound of transformers cooking off as the driving rain clawed its way past their protective shells. They’d explode with these hollow pops that sounded like distant bombs falling—even over the freight-train roar of the wind and downpour. That storm was weak—Category 1, but it was slow, too. It squatted over New Orleans for a full 24 hours.

Isaac knocked our power out for four days. We spent a lot of time hanging out at the law office where Stell worked, streaming TV and eating sandwiches from Cochon Butcher, and on the fourth day, we arrived home to find our porch light burning again. For Ida, Diqah and I got a room on the 20th floor. I’d never been up so high to observe a storm. Our view was of the rest of the CBD—Harrah’s Hotel and Casino, the Hilton, the World Trade Center, and the brown band of the Mississippi reclining in its bed.

The hurricane came ashore like Count Dracula, in the form of a fog. I reasoned that the rain must be falling so hard that it seemed to foam up from the ground. As I stood watching out the enormous window, the hotel rocked back and forth like a cruise ship. We kept the news on, listening to the weather, and I was surprised to see that Karate wasn’t worried. He took the thunder and lightning in stride. It was I who couldn’t keep from staring in horror at the darkening river.

The hotel power went out around ten that night, with the storm still raging. By then, it felt like a giant had mistaken the building for a heavy bag and was practicing its best punches. Karate began to complain at the noise and the darkness and the terror that collected like ice water in my chest. I know I slept, but I’m not sure when or for how long. I dreamed that our room door opened softly the wrong way. Dark figures walked in, looked around. Someone stood at the foot of my bed. Someone else railed at and harangued me, but their volume had been turned down, and all I could hear was the most rudimentary shapes of their words—the sibilants, a plosive or two.

I woke the next morning to see the Mississippi flowing backward.

• • •

We hadn’t bet that the entire city would go dark for weeks. We headed back to the apartment and languished in the heat, picking up donated meals from food trucks around town, swimming in the brackish courtyard pool to take the edge off. We didn’t talk about it—not for some time, but once electricity was restored our home seemed smaller and grimier than ever. It was time for a change.

Of course, storm damage drastically affected the housing stock—that and the proliferation of short-term rentals in town. It was a good thing my own fortunes had already taken a turn for the better, or we would have been stuck in our shitbox for another year. As it was, we found a place and moved in November. That was around the time I got the first notification on Snapchat that Jon Reaux had joined.

• • •

Jon was one of the first people to welcome me into the scene when I started doing standup. Ten years younger than me, Jon had a star quality, a charisma to him, that I found undeniable. He was also lazy, unfocused, and seemed content to fuck around indefinitely. He could also be rude and dismissive, which I didn’t take personally, but it stopped me short of considering him a friend.

I had no illusions about what comedy could do for me. I’d started too late to spend fifteen years in the trenches building my skills until I could tell jokes for a living. I was a writer, and comedy was something I did to blow off steam. I was decent at it—for a beginner—but I had no interest in the social push-and-pull of the comedy community. New Orleans was not the place to make it big in showbiz—it was somewhere to see and participate in excellent shows, and the instant gratification of getting laughs helped ease the pressure of the long waits involved in publishing.

One afternoon back in, oh, 2015, I was asked to perform on the Underwear Comedy Party. This was back when Joe Pettis was running the show, touring all over. I was morbidly obese, and gynecomastia had made my childhood a living hell, so before I got into standup I spent a lot of energy trying to deflect notice away from my size and shape. Comedy taught me to accept myself, that being the center of attention could be a good thing. Performing in my underwear didn’t seem any scarier than getting onstage and talking into a mic in front of strangers, so I agreed.

On the night of the show, I arrived early. Jon was already there, still wearing his white and green work uniform. As my car dropped me off, he leaned against the wall that ran alongside Saint Claude Avenue, dragging on a Kool that looked so rumpled I was surprised it was intact enough to smoke. He was sweating, but it was barely more than eighty degrees out.

He was a good-looking guy. He was almost lanky, but without being tall or raw-boned. His complexion was maybe a shade lighter than my own. He’d worn his hair in an afro since we met—often uncombed. There was a hard, watchful playfulness to his expression.

I offered a handshake, but Jon turned abruptly away. I wavered for a beat, then shrugged, headed inside.

In those days, the Hiho Lounge was one of my favorite places to perform. It was small, but not so small as to lack a backstage. Smoking in bars and clubs had been outlawed by then, but there was a smoky quality to the light in there that made me feel almost like a real comic. The stage, raised a couple feet off the floor, even had a thrust to it.

I sat at a low table by the sound booth and pulled out my notebook to decide which jokes I’d go with tonight. I might stick with a setlist, and then again, I might not, instead riffing on how it felt to stand gigantic and nearly nude in front of the crowd.

A whiff of tobacco smoke told me that Jon had followed me inside. “We came up different.”

I looked up to see him standing over me. “What?”

“We came up different, you and me. Our daddies stuck around.”

It took me a moment to realize what he was talking about, and when I did, I squinted, irritated. “Sure,” was the only response I could think of.

“Where your daddy from?”

I opened my mouth to respond and remembered the handshake he’d rejected. “Listen, man. I’m down to talk, but let me work my shit out first.”

“Yeah,” he said. “You good.” He turned away.

I heard later that Jon was nervous about going up that night. Somebody told me he had insecurities about his own body. It hadn’t surprised me to hear as much because many of the comics I thought would be perfectly at ease in their briefs were ready to jump out of their skin.

Still, I think about that exchange. I think about it a lot.

• • •

After a few years doing comedy, I started experiencing excruciating and unpredictable pain in my jaw which meant I had no idea when I’d have a pain-free five to fifteen minutes that would allow me to tell jokes to crowds. This was a problem I’d had off-and-on for years, but in 2017, the pain grew worse, more consistent.

I started doing comedy less and less. I’d get booked on shows or for readings and have to cancel at the last minute because I couldn’t count on my jaw to cooperate at crunch time. It was time to finish the novel I’d labored over for years.

Jon attempted a move to New York and come back to New Orleans in a couple weeks when he ran out of money. That seemed like Jon all over, but don’t get it twisted—I knew he would be a star. I knew that one day, I’d hear that Jon had been cast on Saturday Night Live or that he was getting a special on Comedy Central. All he would have to do was get out of his own way.

He spent some time back here licking his wounds, and then headed for LA. This time, the move seemed to take. He started performing out there, made friends. While I didn’t follow him closely, it seemed he was doing well.

Then a mutual friend posted that he had died.

It was a waste, an impossibility. I spent hours hoping this was a tasteless bit—Jon trying to learn what the scene really thought of him—but he was truly gone.

Like a rock star, he’d died at 27.

• • •

It was a nightmare looking for a new apartment. Saadiqah and I toured cramped two-bedroom spots without central air, dishwashers, washer/dryers, and half the time, without so much as a fridge. Finally, Diqah and I decided that a large complex might be the way to go, so we toured a place at The American Can, an old factory/warehouse that had been converted into apartments years ago.

The complex is a landmark in itself, situated just across Moss Street from the final stretch of Bayou Saint John, a miles-long waterway that, at one time, had cut clear through New Orleans. The interiors still looked industrial, with painted-over metal sliding doors, concrete or scratched-up hardwood floors, and support columns occupying positions that must have been perfectly sensible when it was a factory, but now stood awkwardly here and there.

The apartment they showed us when we toured was bizarrely shaped, but it had two bathrooms, a dishwasher, washer and dryer. One of the reasons I’d been so slow to leave the old place was that it had an excellent saltwater courtyard pool. The American Can’s pool was larger and lacked a deep end, but it would take the edge off during our boiling New Orleans summers. The only drawback to the place was that it was so close to the hospital.

• • •

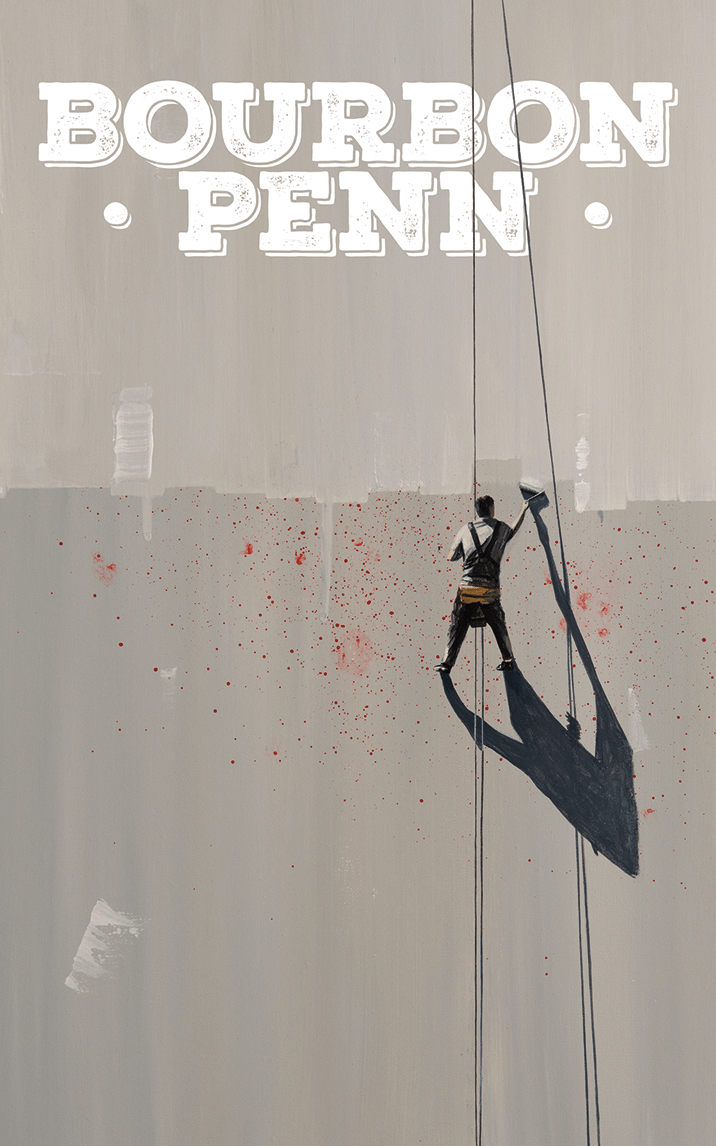

Lindy Boggs Medical Center was once the best place in the region to handle transplants. It was a state-of-the-art facility up until Hurricane Katrina when it became a tomb for fifty patients. I lived in MidCity for about a year in 2009 before I moved Uptown, and I remembered walking by it then. I’d assumed someone would take it over and redevelop it, but nobody did. Instead, it was fenced in, neglected, and mercilessly tagged by street artists like Darpo, Cenac, and Fat Kids.

The first night I walked Karate past it, I had to turn my music all the way up in my headphones. No noise came from the hospital, but it was loud. I’m not talking about the screams and moans of the abandoned dead. It reminded me of being a kid, alone in the house, and hearing the air ring with silence. The lack of noise rippled through the vicinity like a sustained roar. I would have stopped walking by it entirely, but its position meant I’d have to stay off the Lafitte Greenway, which was one of the best neighborhood amenities we had—second only to the Bayou itself.

Besides: I didn’t believe in ghosts.

• • •

I’ve always been more active and capable than my size would suggest. My obesity has rarely kept me from going on walks, swimming, whatever activity I feel like taking. Diqah and I got Karate during the Pandemic because we’re both heavy and we wanted a reason to take daily walks. He was a perfect physical motivator.

We took Karate on longer walks a few times a week. We’d traipse the entire length of the Greenway and back, or head over to City Park to march through the greenery or around Big Lake. This time, we’d walked up to the French Quarter, and the day exhaled boiling crawfish and cut grass. Sometimes, even at a distance, I could feel the hospital drawing nearer, as if in a dream where I stood rooted in place and the complex dragged itself to meet me.

As we walked, my mind slid from idea to idea, working out story problems, weighing this or that career move. As we neared the blacktop where the Farmer’s Market erected itself every Thursday, the hospital felt like a thumb pressed against an Etch A Sketch. It didn’t impede my thinking, but it was a distortion against the surface of my mind.

When we reached Moss Street, Karate insisted on investigating the giant flower sculpture situated near the street. Even with the hospital so near, I felt calm. I let my eyes drift shut and breathed a deep draft of the green city air.

The next thing I knew, Saadiqah glared at me, wide-eyed, as we stood on the greenway on the other side of Moss Street. “Hey, what?” I said. “What’s wrong?”

“That’s what I said!”

“Sorry,” I said. “I checked out for a second, thinking about work.” I realized then that she was holding Karate’s retractable leash and that he was straining at its end, trying to resume walking toward some scent that had caught his attention. The hospital was louder than ever, with the volume and insistence of held breath.

I thought of that scene in The Dark Knight Returns when Bruce Wayne is startled awake by Alfred in the Batcave and finds that he’s been sleepwalking again. I thought of myself standing here in my lounge pants in the middle of the night, staring blankly into the Hospital’s vacant windows, and a cold prickle danced up the back of my neck.

“Sorry,” I said again.

Just before we moved on, I noticed a new Fat Kids tag spreading above the largest windows near the roof of the main building. The tag was angular and ugly—the stylized letters seemed bent out of shape, but the stylization made the words mean something other than what they said.

• • •

Ever since my book came out—before that, even—I’d had a hard time getting rest. It didn’t matter how late I slept or how deeply, I’d wake up feeling tired and washed-out. The situation didn’t seem like cause for alarm. The Pandemic had worn on for years during which the fear of infection or of infecting others had only lifted for a few weeks at a time. Everyone I knew was worn out in one way or another. I tended to draw strength from spending time with my family back in the DMV, and I still felt the strain of missing and fearing for them for so long.

Saadiqah had been in New York for a few days when my gut started bubbling something fierce. I sat on the toilet, holding my belly and hoping whatever this was would respond to a little Pepto Bismol and some rest.

When I stood up and saw the toilet, I began to think otherwise. I tended to bleed now and then, never terribly much, but sometimes enough to excite my inner hypochondriac. There didn’t seem to be any blood this time, but there was a black, tarry substance I’d never seen before, and as I stared at it, I felt dizzy.

It wasn’t just that one trip, either. It was a string of them over the course of a day and a half. I began to feel even more tired, more out-of-sorts than usual. My memory, my consciousness began to waver, but how bad could the situation be if there was still no blood in the bowl? It took me a long time, too long, to haul myself half-naked into the bedroom. I stretched out diagonally across the king-sized mattress and felt the ocean of my consciousness lapping gently against the vault of my skull. I thought of Jon, dead for years. I thought of the quiet sands of the Sahara, and the pocked, mute surface of the moon. My thoughts circled tighter and tighter, then elongated as they drew down and away.

I hoped, as I passed out, that I would wake again.

• • •

I don’t remember calling an Uber. I don’t remember getting dressed or locking the apartment behind me. The next thing I knew, I was half-sitting, half-leaning to my left in the backseat of a Honda, staring at Saadiqah’s photo as I waited for her to pick up.

“Hi, you!” she said. “How are you?”

“I think I’m pretty sick,” I said. “On my way to the hospital.”

“Which one?” she said calmly.

A glance out the window told me we were headed down Claiborne toward Harahan. “Oschner, I think. The big one.”

“I’m coming.”

“It’s probably nothing,” I said.

“Is it nothing?”

I felt heavy, and everything was slow.

“No.”

• • •

Saadiqah and I met at a cookout out back of a murder apartment at the edge of the French Quarter. The killing was big news in the wake of Katrina when I moved to town. A guy had murdered his girlfriend with whom he had ridden out the storm and its aftermath. He hacked her up in the bathtub, then stashed her head in the oven and painted the bathroom and kitchen black. When he was finished, he got a hotel room up the street and spent every dime he had on pussy and narcotics before confessing everything in a note and jumping from a ninth-floor window.

A comedian friend of ours moved into the place years later, and when he invited me to a courtyard barbecue, I had to go. Saadiqah felt the same.

I’d only lived in New Orleans a few years, and I didn’t believe in ghosts, so I wasn’t surprised to find that the place bore no stain from the murder. It had been renovated, repainted, and outfitted with the latest appliances and décor. Vince was one of those comedians who moonlighted as a lawyer, so he had the place looking nice.

I recognized Diqah from a video I’d seen on Instagram where she danced her ass off with pompoms. She was tall and broad with sweet, heavy curves, dark dark skin, and bright, luminous anime eyes. Her complexion reminds me of my favorite soul song, “I’ll Run Your Hurt Away” by Ruby Johnson. Like the vocals, Saadiqah’s skin is rich and sonorous, and every time I touch it, I feel like I’m drawing a horsehair bow across cello strings.

She wore a fresh fruity scent I couldn’t identify, but it was May, and it mixed with the faintly metallic edge of her sweat to make my head swim. All evening I found myself watching her closely, losing track of what she was saying as I tracked her movements and the motion of her lips.

We learned in conversation that we lived mere blocks from each other Uptown, so at the end of the night, we shared a cab. She sat quietly in the backseat, her fist balled loosely on her dark and ample thigh.

I said, “Saadiqah Ogunde, I think you’re finer than a year’s worth of speeding tickets.”

She tried not to laugh but lost the battle. “Do you, now?”

“I surely do.”

“… Then prove it …”

Our first kiss deepened quickly, and afterward I told our driver we’d only need the one stop. Diqah didn’t get home much after that. About a year later, she moved into my apartment because I owned the nicer bed.

• • •

By the time Diqah joined me, I’d been admitted to the hospital, and I was on my second blood transfusion. The doctors felt reasonably sure that I had at least one ulcer and had done for some time. The black, tarry substance coming out of me was old and digested blood—and my hemoglobin was comically low. Our nurse Ms. Genevia was surprised I could speak or open my eyes.

I don’t like to think how all this would have gone without Saadiqah. Or about the fact that sometimes there were three of us in that room.

• • •

Jon’s death was heavy on the comedy scene. He wasn’t the only one who’d left us over the years, but his absence was the most keenly felt—at least for me, and the comedians close to him.

I’d been told so often throughout my life that my size endangered my health. I’d tried diet after diet, and even when I worked out, all it got me was strong. That should have mattered to me more than anything, but what was all that effort worth if every tenth person I encountered still treated me like a circus freak?

That spring, everyone was talking about Ozempic, Wegovy, the new semaglutides that were helping people lose weight after lifetimes of trying. I’d seen crazes come and go. I remembered fad diets, new workout systems, and nutrition plans. I was more comfortable with my body, with myself, than I’d ever been, but winding up in the hospital spurred me to act. I asked my doctor for a prescription and started taking it—since I was diabetic, I didn’t even have to pay.

For weeks, nothing happened. I honestly don’t know what changed. Maybe it was that I recovered enough to boost my activity level without realizing it, but the weight started falling away like it almost never had.

Almost.

When I was twelve, my family moved to Paramaribo, Surinam because my dad was posted at the American Embassy there. With the boost in income, my family could hire me a personal trainer, and Mr. Leslie put me on a diet consisting mostly of bread and cheese with a normal meal every evening. I was also on my school’s football team—I wasn’t half bad, for an American.

I lost all the weight. All of it. People started treating me differently. Girls responded to me. I’ve never told anyone, but it broke my heart. When we moved to Tunis two years later, I gained back much of the weight. I didn’t do it on purpose, exactly, but it wasn’t an accident, either.

• • •

Diqah was younger than me by a few years. She was born in London to Nigerian parents and moved to Texas when she was twelve. That was the clincher for us, early on. She understood the trauma and excitement of moving to a strange country at a vulnerable age. Like me, her classmates had found her terminally weird, and she had faced the awkwardness of her teen years without the comforts of a home. She understood what it meant to be a fat kid.

I was seeing someone else at the time, had been for years. That relationship wasn’t giving me what I needed, but I cared deeply for my partner and understood that neither of us was perfect. When we started dating, I explained to Diqah that I was polyamorous and that, for me, it wasn’t so much a practice as it was an orientation. I felt I should be worried when Saadiqah said she was the opposite, but we had such fun together that my desire overrode what I thought of, at the time, as good sense.

I see how the world treats Black women. Dark-skinned ones, especially, and I hate it. I can’t help but link it with the way I’ve been treated with my round bulk and manly tits. The fact that Saadiqah had ever been made to feel unattractive was absurd.

Our first kiss felt like celebrity. Like flashbulbs and red carpets. I felt like my best self, like the man I aspired to be. I felt transmuted, made beautiful by a sorcery of need. Denis Leary used to say that smoking builds character because, “Everyone deserves to know what it’s like to want something more than anything else in the world and to get it over and over again.” I never liked that joke, but I respected it, understood it. Saadiqah completed that understanding.

That’s partly why, when she told me that she needed monogamy, I agreed to her terms. I simply could not let her go. The difference in our understanding of relationships and desire worries me from time to time, but I’ve never regretted my decision.

Not once.

• • •

Sleep got rocky when the weight started melting off, and all the while I kept getting those goddamn Snapchat notifications from “Jon.” I never figured out the app. I got it because most of my comedian friends were on it, but I knew as soon as I downloaded and took a look at it that I didn’t care to understand.

My doctor watched me closely, testing my blood every couple weeks, but all my numbers did was improve. Blood pressure dropped, evened out, A1c plummeted below the diabetic range, and by October, I’d lost roughly 90 pounds. I had a lot of clothes that stopped fitting during the Pandemic, and every so often, I would try to and fail to get into a shirt I hadn’t worn in years. One afternoon, Diqah and I attended a cookout at the Peristyle in City Park, and all of a sudden, a pair of slacks I hadn’t gotten into since 2019 swam on me—large enough that I knew I couldn’t dance without a belt or suspenders.

My body felt stronger—younger, even. But there was a shadow at the edge of my consciousness: Before she left me, Stell had said, “There’s a reason you haven’t lost weight since we’ve been together. Something in you likes you this way. It wants you to stay sick.”

It had crushed me.

I was proud of my achievement, shedding so many pounds, even with the help of a wonder drug, but I was conflicted. When I looked at myself nude in the broad bathroom mirror, saw myself shrinking, a small voice whispered at the edge of my mind: What are you doing? If you’re not big, what are you? Why would you want to be small?

• • •

There’s a dream I’ve had since I moved to New Orleans: I take a wrong turn walking to work. It doesn’t matter where I’m working at the time. The dream is situated in an eternal present where I leave home every day. I take a wrong turn somewhere in Black Pearl or Gentilly, or in the Bywater, and the street signs stop making sense.

I keep walking as the hour creeps later and later. I check my phone to find I can’t read the time. The readout shows digital runes like the wrist display in the Predator movies. No matter what I see there, it spurs me to turn more often, losing myself more and more. After a while, it’s evening, and I still haven’t made it to the office/café/school, and I know I’m going to be fired. Eventually, I come to a motel, the same one my brother and I stayed in the first time we visited New Orleans in 2003.

Nobody’s at the front desk, so I look around the property for someone who can give me directions. Eventually I come to a room with an open door, and inside are three cops with deep shadows distorting their faces—almost like bank robbers wearing pantyhose masks. The policemen are busy subduing a lanky, light-skinned Black man with an afro shorter than Jon’s was last time I saw him. He’s wearing a gray tweed blazer with elbow patches even though the air smells of rust, orange oil, and baking heat.

One of the cops kneels with his knee pinned against the man’s back. The others are speaking gibberish, brandishing their batons. Sometimes they hit the man, and he cries out, his voice high and thin like an infant’s. There is an awful familiarity to the vision. It frightens and saddens me, but it isn’t a shock. I know the man being beaten is dead, has been for years, and that this is the Dead Side of New Orleans.

One cop looks up at me. He stabs the first two fingers of his right hand toward his eyes, then points them in my direction. I’m watching you. I’m watching you. I’m watching.

One day, I’ll die, and I’ll return to this room to take the man’s place. Every time I have the dream, I wonder whether that day has already come, if this is my chance to relieve him.

It never is.

• • •

I started awake to find the air dancing invisibly. Diqah slept next to me, snoring lightly, lying on her side as if she’d fallen from a great height. I slid the fingers of my left hand into hers, which usually calmed me after a nightmare, but this time, nothing changed.

It took me a moment to realize it, but my phone had just chirped for my attention. It was set to Do Not Disturb, so no notifications should have come through. Moving slowly, as through water, I picked up the phone to read the screen. I expected it to tell me again that Jon had joined Snapchat, but instead, the notification read, Jon Reaux has sent you a chat:

u busy???

I stared at the message for a long time, fully aware what my response would be. Finally, I typed it in:

no wazzam?

His response took long enough for me to wonder whether one of our old mutuals was pulling a shitty prank.

fat kids

come 2 fat kids

sumn to show u

fat kids

fat kids

fat kids

fatkids

fat

fat

I sucked my teeth. People talked about closure. We talked about symmetry. Story brain and pattern seeking were baked into our collective psychology, but if life had taught me anything, it was that life was not Story. Life was messy. Humans applied structure to the stories we told ourselves so that we could live with our pasts, live with ourselves. The dead didn’t communicate through phone apps. They didn’t resolve out of the mists of uncertainty …

Unless they did. I’d been wrong before …

k. gimme a min.

• • •

When I stepped onto Toulouse Street, the hospital was quiet—which worried me more than if it had been at a full blare. I cut through the Wrong Iron’s parking lot to the Greenway and saw that the complex wasn’t abandoned anymore. No graffiti. No broken windows. The lights inside were on and burning.

The sight hit me like a sucker punch. It was as if I saw into an alternate New Orleans where nobody had been left for dead or euthanized when the city drowned.

Years ago, after Stell left, I would go for walks around Central City because my apartment was too small and close for the self-loathing I felt. I’d take photos of blighted buildings and post them to social media with the caption, “ME IRL.”

I pulled out my phone to aim it at the hospital, but on the screen, the place looked as it always had. Windows gaping empty, chain link fence bordering Conti, tags crowding every surface. I photographed it anyway, nine or ten times, posted each one without context or explanation. I didn’t realize until I’d finished that if Diqah woke to find me gone and saw the posts, she’d be terrified.

I knew I should turn around, return to bed, keep inhabiting this world—but I didn’t. I cut through the vacant lot the bar used for overflow parking and crossed Conti to the complex. No tags stood out on the hospital’s outer walls, but I knew where to go.

• • •

I saw a ghost once. I saw something, I mean.

Before I moved uptown, I lived on St. Peter and Dauphine. It was a lovely little place with black and white checkerboard linoleum in the kitchen, stainless steel appliances, and a few of those bricked-up fireplaces you see everywhere in New Orleans. Back then, my morning routine had me waking early, making myself a cup of tea, and spending an hour sipping thoughtfully and planning out my day before I had to leave for work.

One morning, just like any other, I had made my tea and turned around to head back to my room, but the sight of a strange white man standing in the dim of the living room stopped me in my tracks. He wore old-timey clothes—breeches and a waistcoat with riding boots—and his hair was tied back with a maroon ribbon. He seemed as shocked to see me as I was to see him.

I cried out. It wasn’t a shout of terror, it was involuntary, like a fart or a sneeze. I jerked my tea-bearing hand in the air and spilled some on my wrist. It stung me at a remove—I registered the pain, but it didn’t make my list of priorities.

The man and I regarded each other for a few more seconds, and then he wasn’t there. He didn’t disappear or fade, he just wasn’t there anymore. Instead, there was the collection of shapes—the outline of my brother’s L-shaped desk and executive chair, a bust of Mozart sitting on the mantlepiece ten or eleven feet in front of me, the ferret cage …

From time to time, our blender would turn itself on, and we would joke that a ghost was trying to make itself a margarita. Neither of us got a haunted vibe from the apartment, and as transplants to the city, we’d brought with us a healthy dose of DMV skepticism.

I can’t say for sure that what I saw was a ghost. The man I saw didn’t look dead. His cheeks were ruddy. His hair—it seemed like real hair and not a wig—was carefully combed and tied. His clothes weren’t meant for the grave. When I recall the incident, his expression clinches it for me all over again. He was truly astonished—as if I had appeared to him. He was probably appalled to see a Negro in pajamas and a dressing gown make himself a cup of tea like he owned the place.

This is what I mean when I say I don’t believe: I don’t know what I saw. I don’t understand the circumstance. Sure, I could assume I’d seen the spirit of a man who had been dead for hundreds of years, but if that’s possible, then it’s also possible that he and I somehow saw each other across time. That both of us were perfectly at home in our eras, going about our daily lives, and the veil of years had thinned enough for us to see each other.

There was no message attached unless we ourselves were the message.

• • •

A few weeks ago, I watched four teenage boys pry a back door open and head inside the hospital. I never saw them come out, but if something had befallen them, it would have made the news, right? I try not to think about the fact that these were a bunch of Black kids. What if nobody had missed them, and they had disappeared like smooth stones dropped into a pond?

People who have ventured inside claim to have heard the screams and sobbing of stranded patients, seen spectral doctors scrambling in a losing battle to save their charges. A friend of a friend even claims to have been chased out of the complex by “a fuckin demon, my nigga!”

None of those stories sound right. In them, the teller knows exactly what’s going on. They’re adamant about their experience. I know what I saw, baby! It’s the certainty in anecdotes of the supernatural that makes them so hard for me to believe.

Our bodies shape the way we experience the world. The way we propel ourselves across it, communicate with each other, with other creatures. How can it be so easy to converse with bodiless spirits? People tell stories of encountering ghosts, cryptids, angels—and their tales are strangely basic. People in the Bible collapsed with seizures when heavenly spirits appeared, and you’re telling me that when one turned up at a red light and leaned into your passenger window to tell you to turn left instead of right at the second light down that you felt just fine?

• • •

Dark fell on me like a velvet curtain when I stepped into the hospital. It was like being waterboarded by unsight. I still felt a floor beneath the too-thin soles of my shoes, so I trusted my body to anchor me to myself, to something familiar. My footsteps made no sound.

Before we moved in together, Stell lived in a slave-quarter apartment in the Vieux Carre. Her place was on the second floor, past the courtyard, but to come and go, we had to use a narrow hallway to access the street. The overhead light in there was broken and the landlord had never fixed it. That corridor always seemed much longer and darker than it should have—almost like a metaphor.

That ice-water sensation filled my chest again. It buoyed my heart, radiated through me in waves, and every time I felt the darkness lap into my throat, I expected it to wake a raw red scream. Just when my unused voice began to feel like it would choke me, a breeze gusted my way carrying the aromas of coffee, steamed milk, and frying dough. All at once, I found myself in City Park, standing on the sloping bridge that ran between the sculpture garden and Café du Monde.

My surroundings resolved like the shifting of a dream—that moment when one place becomes another, when one life and history fade in favor of some revised circumstance. I don’t know if other folks dream this way, but I’ve dreamed entire lifetimes which segued into other lives, complete with their own memories of fictional pasts. I shivered as I waited to understand where I was, what I was doing, and all I could think about was Jon’s only TV appearance.

Just before I quit comedy, a documentary production had come to town. They were taking looks at comedy scenes around the country, and a comedian couple who actually owned a house had put on a show in their backyard, served pizza, packed the place out. Most anybody who wanted to had gone up. Jon had performed one of his best sets ever, where he complained about wearing a paper hat to serve coffee and beignets here in the park. As I crossed toward the café patio I was sure I’d see Jon wearing his uniform, his ridiculous hat canted jauntily on his fro.

He wasn’t in the abbreviated parking lot by the coffee stand or on the patio with its crazed ochre-and-yellow floor. Only one seat was occupied, and the man sitting there was not the one I wanted to see.

Meeting yourself is not like looking in a mirror. It’s not like watching yourself on a screen. To see your living breathing doppelgänger filling out a wrought-iron chair, his rolls bunched beneath his arms is— He must have had his hair cut just that day; he smelled of Barbicide and Afro Sheen. The slight sourness of breath told me he still smoked cigarettes from time to time. The sight of him was worse than disorienting. It was sickening. Especially when I realized that some small part of me had expected this.

When I was very ill from the blood loss, Saadiqah told me I looked pale. That pallor, that washed-out quality wasn’t visible to me in a mirror—but it was now. So was the difference in weight. One look at this other self told me he weighed significantly more than I did.

I had frozen in mid-step. My body wanted to continue past the café, past the Peristyle, and on home as I had so many times on my walks with Karate—or just turn around and head the other way—but I couldn’t. The paralysis only broke when I resumed my approach.

I sat across from him.

“It worked,” he said evenly.

“That was you contacting me? Pretending to be Jon?”

He shook his head. “Jon helped. He’s here somewhere.”

“Working the café?”

He scowled. “Of course not,” he said. “Would you?”

“No, but— I don’t know how this works.”

“Would it help if I told you it was all in your head?”

“Is it?”

His grin was a humorless display of crooked teeth. “Not at all.”

I shut my eyes, took a steadying breath. I was terrifically angry. Baldwin said that to be a Black man in the United States and even a bit conscious was to be in a state of rage almost all the time. It was one of those truths that made me feel spied-on—one of the truths that made Baldwin difficult for me to read. This anger, this loathing, felt dirty and craven.

I opened my eyes. “What do you want? An apology?”

“If that’s your way of asking whether you killed me, the answer is yes. You did. But it took more than you. More than a simple desire, or even your action. It was a million little things. I suffocated. I kicked, I screamed, and I begged. I told you stories.”

I shook my head. “The stories are mine,” I said. “Only I could tell how I survived. How I’ve kept everything from fucking caving in! How I—how I—connected with something beyond me. Only I could tell what it felt like for me to live divided from everyone and everything.”

“I was there with you.”

“Is that what this is? You want me to tell you I miss you?”

“It’s not that you’re killing me that bothers me,” he said. “It’s that you’re so cruel about it. What did I do to deserve what you’ve made of me? Why do you want to lock me in that hospital? Why do you want me in that motel room getting killed over and over by those cops?”

It took effort to keep my shoulders from rising to my ears. “I won’t do this with you,” I said. “You know why.”

“Say it.”

I shut my eyes again, inhaled through my nose. The trickiest thing about rage is that it is often a mask for deep sorrow.

“Stell was right about me,” I admitted. “I couldn’t get rid of the weight because something bad was alive in me. Some small sniveling part of me that held me back. You.”

“You decided to kill me as soon as you could figure out how to do it without killing yourself.”

“Yes,” I said. “I hate you. Oh, people are mean. Oh, the world is hard! Oh, people don’t understaaaaand me. Nigga, fuck you.”

My words fell onto the table between us and just lay there for a moment as we regarded each other in silence.

This wasn’t what I wanted. I had hoped for some impossible closure with Jon, or my memory of him, not a confrontation with my own self-pitying ghost. I’d been so proud, believing I’d transcended the worst of my limitations, but how true could that be when I looked on myself with such loathing and disgust?

“It wasn’t my fault,” he said. “What happened to us wasn’t because of me. Our pain didn’t come from me—not at first.”

“So what?” I said. “You’re the part of me I can get rid of. I could say I didn’t know I was killing anybody. I could say I didn’t mean to cause you pain.”

“Lies,” he said.

I nodded. “Yeah.”

“Good luck getting out of here without me,” he said. “You pretend nothing good in your life came from me. Like I never taught you to tell jokes or write poetry.”

“Come on, Alex,” I said gently. “You know good and well that I would give all that up in a heartbeat to be rid of you forever.”

His face fell. More than anything, in that moment, I was amazed by his anguish and dismay. How could a piece of myself misunderstand me so thoroughly? The difference between us was not that I was better or more capable than he. The difference was that when I left here, to walk back into the dark of the hospital, I would crawl through that blackness if I had to, knowing that if I kept on, crossed the Greenway back to my apartment, I’d find Karate snoring in my red leather chair, yipping softly as he chased rabbits through his dreams. Diqah would be lying on her right side, her smooth left leg bent at the knee, her pillow clenched like an old-fashioned telephone receiver between her cheek and her shoulder.

I don’t tell you this to prove myself a better man than that other self or to reveal that I am worse. I tell this story as faithfully, as truthfully, as I can, because it is the least I can do for the man I was.

He’ll never rest in peace, and he deserved better.

Copyright © 2024 by Alex Jennings