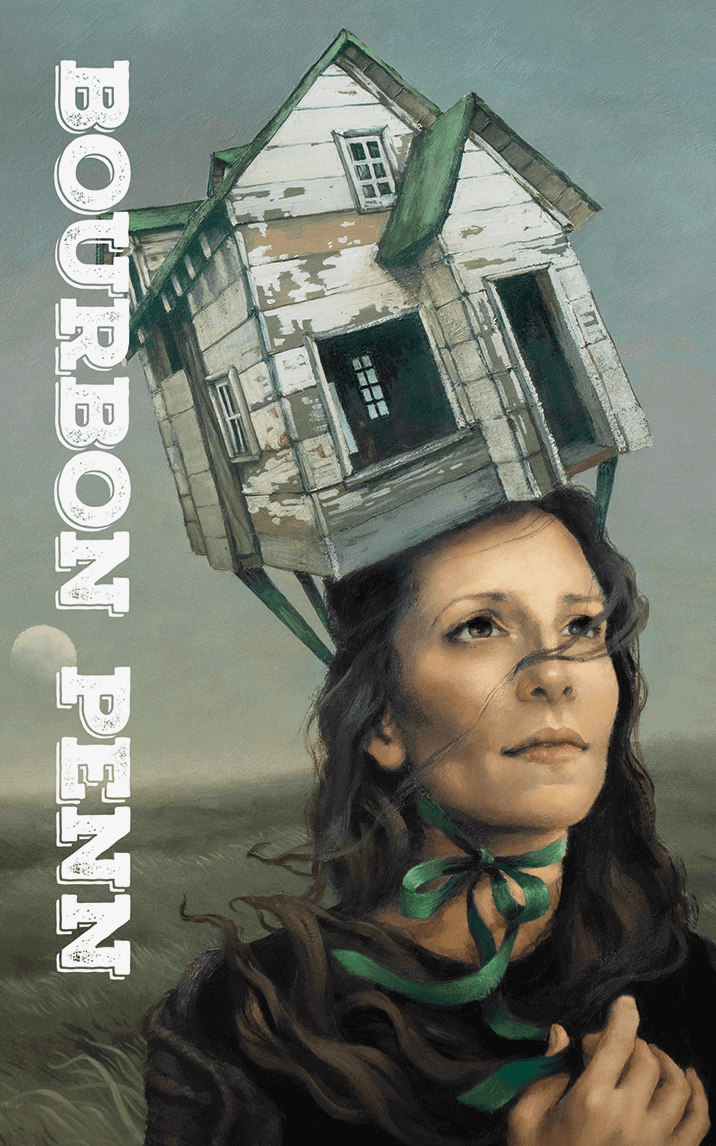

House Traveler

by Thomas Ha

The five of us were gathered on the floor of one of the last houses, trying to decide which of the group would be the one to go outside. Sitting around an electric camping lantern, our legs crossed like children, it almost felt like we should have been sharing stories—the way people used to before the end of everything. I mostly sat and listened to the others talking, though I had some trouble comprehending each word individually. My mind felt much like the thin fog curling just outside the dirtied panes. But I understood clearly what it meant, when the man in the tall hat pointed a finger at me.

Yes, of course.

He believed I should be the one to go to the Liar next. And I wasn’t sure why, but it made a certain kind of sense to me.

I should be the one to go.

Yes, of course.

• • •

They gave me the knife and a small sheath-holster where I could keep it, on my belt. A sign of trust, letting me leave with the group’s knife. They also gave me one of the whiskey bottles from our basement, and who knew how many of those were even left?

Are you ready?

I wasn’t. But I nodded at the man in the tall hat. It was a rare thing to go to the Liar, and he wouldn’t make me travel the houses unless we were desperate. He rested a hand on my shoulder and told me that if I returned with nothing, there would be no shame. Others had met with the Liar and returned with nothing, and that was no shame.

No shame.

The woman with the scarred cheeks led me to the front door, and the bearded brothers trailed behind me in case I tried to run. She placed her hands on mine and said a few gentle words of encouragement, then let me go out onto the porch into the gray neighborhood, where the husks of houses waited for me like shadowy faces, leering.

On your way with you, the scarred woman said.

—On my way with me … I replied.

• • •

The stars overhead were red and streaked like weeping blisters, and the dark clouds looked something like scraps of bunched skin. Beyond the neighborhood, what little I could see was an infinite flatness peppered with the shadows of other house-shapes, which were blurry and dizzying from where I stood.

I didn’t even remember what a neighborhood was supposed to look like.

I just knew it wasn’t supposed to look like this.

Down the street, as I went slowly past the nearby houses, I could see into the gaps where doors should have been, now looking like large mouths hanging slack. And in the darkness of those entryways, there they were, just like he’d described.

White things, light shadows, moving about, here and there. Some by the filmy windows, others circling the edges of the yards. The pale figures blinked and flickered almost in a beautiful, disconnected movement.

Don’t let them distract you, when you’re out there, on your way.

The man in the tall hat had warned.

They aren’t here, the white ones—only after-images of lost places and nothing more, so keep going along the street, on your way.

The man in the tall hat often said things like this. What was outside the house we lived in, like he had been there often. And he repeated them most of all to me, like I was a child who didn’t know well enough to follow directions.

Remember that, on your way.

—I’ll remember that, on my way, I had replied.

The street ahead curved to one side, then the other side, before opening into a rounded cul-de-sac. The half-dozen houses surrounding this part of the neighborhood were stretched and angular. One of the houses was burnt down to its blackened, grainy frame.

And it was there, in the dead end, on a road and on a picnic blanket, that the Liar waited.

When I saw her, she stared back at me, and smiled and waved.

• • •

What did I expect the Liar to look like?

I didn’t really know.

The other night, when I’d gone to the den for my training, after the bearded brothers had pushed the rag into my mouth and tied me to the table, and the scarred woman put the helmet over my skull and secured the leather strap under my chin, the man in the tall hat explained that the Liar could be many things. He said it just as he administered my needle-medicine, with that long, cool point sinking inches into my chest before the burning came like a burst of color inside of my head.

You may see a person, you may not. You may see an animal, you may not. You may see an object, you may not. You may see an angel, you may not.

Without knowing how I knew, I did understand, somehow: This woman was the Liar, sitting there, in this cul-de-sac, in front of the burned house, on the blanket, on the road.

She beckoned.

I approached.

And I joined her on the crumpled blanket.

She held out a soot-smudged hand for the whiskey bottle, and I gave it to her, watching as she poured two plastic bowls full and waited for me to drink first, as was the custom. Just like the man in the tall hat and woman with scarred cheeks did with the other liquors in our house when they had their deep conversations, separate from the rest of us.

They sent you, she said.

—Yes.

To beg my help.

—Yes.

I tried not to dwell on my sheath-holster or the knife within too long. She was the kind of being that could sense those things, they said, and I didn’t want her to perceive any sort of threat.

How long have you been with that expedition?

I couldn’t recall, and I told her as much. I wasn’t sure why I answered honestly, but it felt like if I were going to do this, I should speak only the truth.

Who did you lose?

—Lose?

In the worlds before this one, who did you lose?

—I don’t know, I responded the moment the conclusion came to me, like the underlying answer, if it was even there, had already slipped by me like a moth that was too quick to catch.

Interesting. The scientists you’re with, they scrubbed you clean.

—They did?

Your group, they wiped your mind with modified neural monitoring equipment. I can’t see many memories in your head.

Was that true?

Something in that did seem to be true, to me.

I thought again about the helmet, that needle, the pain—each time they took me to the den for training. Or, at least I think they said it was training for traveling the houses. But it was possible they also mentioned something about breaking associations, de-linking certain neural pathways, that all sounded vaguely familiar to me now.

Your friend said he might do something like this. An experiment. The Liar drank. There are risks. But it could help. Did he tell you how it works?

—How it works?

It was possible, likely even, that the man in the tall hat had explained, but I couldn’t be sure. He had a tendency to explain many things over and over again.

You have until I finish the bottle, the Liar replied. This will keep me occupied, as well as dampen the communion between us. You can try to go into the houses there and take what you want in the meantime. But remember. Until I finish the bottle. That’s the time that you have. Until the bottle is gone.

Yes, they had told me how this would go.

The Liar would drink from the bottle we had offered, and as she did, things in the houses would begin to change, much as they did when the world ended before. I would not have long to see what else was out there, and it would not necessarily work. Not everyone had success with traveling, the others had said. But I stood, determined to try, and the Liar looked up past me at the red stars above.

You know, everything here is a representation of a kind.

—A representation … I said.

When your species interacts with me, I amplify, but I don’t create, It’s only you. Understand?

—Only me. I nodded.

And because they cleaned out your memories, there will be fewer symbols, but those symbols will be quite powerful, do you understand? They may have greater effect than they otherwise would.

—I see, I said, though I had not even the slightest idea what she meant.

She looked at me with pity, the way a person might look at an uncomprehending dog.

Go.

I still don’t know how I chose the particular house.

But something about the crooked fascia and the quaint curved door drew me to it. Or maybe I just walked to the house that was, not the closest, which felt silly to choose, but the one next to that, so I would not be accused of going with the first one I could.

I waited before the door and gathered my thoughts.

Then I left the neighborhood.

• • •

The sunlight was the first thing I noticed when I passed through the door.

There was true sunlight in this house, both clear and warm—no swarming torrents of dust or ash or flakes of plastic drifting across the hallway. The floors were an unbroken, rich wood, and everything smelled like some kind of fruit—oranges? Lemons? There was also a sound of a machine out back, something people once used to cut grass in their yards, I thought. Good, that someone was working outside rather than in the house. And that was good.

I crept up a set of carpeted stairs and into the rooms.

The group had told me that the best thing to do was to find the closets, look for bags, something light and easy to carry. In a bedroom, I found a duffel, and some coats and jackets. I put on as many of those as I could wear.

In the bathroom down the hall, there were painkillers, some bandages, rubbing alcohol, burn ointment, which I threw into the duffel bag. Back downstairs, I found the pantry. Some canned goods. Noodles. A good metal pot and a frying pan. Some batteries. Flashlights. Matches. I was almost out of room in the bag. But I had just enough for a few bottles of whiskey that were stored in the upper shelves.

The man in the hat would be very happy about that, I thought, as I left the house. Very happy about it, yes.

The sound of someone cutting grass in the yard seemed to stop and die out into a thick quiet just before I left.

• • •

Back outside, in the cul-de-sac, the Liar was still drinking. Because she was a thing that was not like us, she did not seem to stop and pace herself, her body, the way the man or woman in the house did when they drank the other liquors. Instead, the Liar drank steadily and constantly, like a machine filling itself with operating fluid.

From what I could see of the bottle, there was still time. So I went on, to another house, across the way, this one bigger and possibly older, with the dried ring of a wreath around an iron door knocker.

The new place, the new house, where I entered was a little colder than the one I had been to just before. The sunshine was still there, still clean and bright. And the structure and layout seemed vaguely similar. But everything in this place felt muted, grayer, and I could hear a kind of siren wailing somewhere very far off.

This time, I went through the living room, thinking the others would want books, maybe playing cards if I could find them, so I rooted around in the desks and the sideboards, as well as other spaces I thought those things might be.

“What are you doing?”

My hand went to the sheath-holster on my belt when I first heard that voice.

But it was just a little boy, watching me from a seat at a table.

“Nothing,” I answered.

“Are you going somewhere?” he asked. Messy hair, a gap where his front teeth should have been, he sat in a chair much too large for him, drawing on a piece of paper.

It had been a very long time since I’d seen a child, and I’d forgotten, I think, their strange proportions. The big round head, the big eyes, skinny limbs. And I noticed how his voice was soft and unafraid and seemingly familiar with me, like he was perfectly at ease.

“Just a walk.”

“Oh.”

The boy’s pencil danced across the paper, waving back and forth, and he hummed a little nonsense tune as he scratched out different figures across the white. Something about that humming, that tune, made me stand still, like I had just touched freezing cold water and was chilled through to my stomach.

I felt tears in my eyes and, for whatever reason, could not bring myself to turn away.

“Can you …”

The boy tried erasing something but did not have the control to do it, the paper continuing to slip one way and then another as he struggled.

I put the duffel bag on the floor, took the pencil and gradually erased an errant line from the paper. My head hovered near his. Something about this felt like a motion I had gone through many many times, so that I remembered it, not in my head, but within my finger bones. I brushed the little bits of pink rubber off the page. The line was still faint, still visible, but now he could draw something new over and around it. He took back the pencil and continued to scratch away.

“Thanks,” he said.

I sat down in a nearby chair, and I looked at the boy without saying anything else. I don’t really know how long I was there, sinking under the weight of the coats, not really thinking anything specific about the boy, no real questions or observations, just watching as he drew.

When he was done, he grinned and held up the paper for me to see.

He had drawn vehicles and other machines, with guns and metallic appendages on them. They were surrounded by small groups of men who were all wearing similar triangle symbols, which I took to be some kind of military uniform.

When I looked closer, I noticed winged creatures in the drawing, too, like unusual birds, that were fighting against the men, or maybe with some of them, very difficult to say. But the winged creatures were much larger than the men and the vehicles, even.

“Mr. Smolin told us we don’t need to be afraid. And I wasn’t … but some other kids were.”

“Oh.” I nodded.

“He says the war isn’t anywhere near us. And it’s not going to be near us, probably.”

“Probably, yes.”

I agreed but wondered if this was one of those things, those signs, that tended to show up in the houses—an indication of how this boy’s world was going to end.

• • •

There were usually hints, the others had said, of things that went wrong in these other worlds inside the houses. And my group never talked about wars or machines or birds.

It was not that way things ended with us. That much I knew.

Things went bad after the Liar arrived, from some other place behind faraway stars. We made and remade and unmade too many things with her, I think. On purpose, but, just as often, by accident. Each time we visited with the Liar, until—with so many changes and mistakes—we were left with the nothing that we now had. These strange neighborhoods, a few lingering groups of men and women, and the Liar there to take the occasional bottle of whiskey from us if we still dared to commune.

Thinking about these things, remembering some of what happened before, made something happen here, too, I realized. I began seeing a strange whiteness outside the kitchen windows—something like a small crack forming in the pavement of the sidewalk, but in a jagged and orderly way, like a pattern.

Perhaps this was why the man in the tall hat and the others did not want me to carry too much in my head when I came into the house. Because the things that I thought, and even things I didn’t know that I thought, were beginning to puncture this other place. For a brief moment, I thought I saw something with wings moving in the sky, like a creature made of static, up there, in the clouds.

I grabbed the duffel bag and stood from the table. The sooner I left, with these thoughts of mine, the more stable things here would probably be.

The boy did not turn to watch me go, instead, sitting and continuing to draw and hum that strange tune, just a little off-key.

I thought about saying goodbye to the boy.

But it felt like the wrong thing to do, so I left.

• • •

The Liar remained perfectly still when I emerged from the house. I sat down with her, trying to remember everything I could about where I’d just been.

The bottle was nearly empty, and the Liar drank at a slow but steady pace. We sat for a time, and I looked at the stars, which now struck me as a strange pale green, like a moss or little stones rather than the angry red I remembered.

A house. The Liar said. Four walls, a roof, maybe some doors or windows. Just a slight separation from everything outside. There is no meaningful difference between house and not house. Just a container. A limiter. A form your mind tries to fill. But there is no difference. You, them, there, here. No difference.

—But … there was … in there, a boy. And I wonder, would he be there if I were to go back into that house? And if I went somewhere else, another house, another street.

The Liar stared through me, like her eyes were pressing up against the inside of my skull.

We are entangled, sometimes, no matter the shape of things. Even though there’s no meaningful difference between you and a boy. So it may be as you say, that you would find him there and elsewhere. But only you know that, not me.

The Liar seemed almost finished drinking, a kind of sleepy relaxation to the way she sat, and I sensed I should probably leave.

—Why are you here? I wondered. In this neighborhood. With us.

The Liar’s expression made it seem like she’d been asked this before but did not care to elaborate. “Why” is a thing for you. It all just is, for me.

—All just is. I muttered, not knowing in the slightest what to make of what she meant. I thanked her and began to walk back up the street, which seemed straighter. No noticeable bends to the path like before.

And I hurried because I thought I noticed something flickering and floating between the clouds. Something white and winged that had not been there before, but felt like it was watching me closely from above.

• • •

It worked? You went through?

The man in the tall hat had been standing by the door, waiting, when I entered the last house. He and the scarred woman laughed when I opened the duffel bag filled with supplies. The first aid, the food, the cookware, the whiskey. Every new thing they pulled from the bag filled them with a lightness and relief.

This will last us a little while.

—Yes, I agreed. A little while. I think so.

They were happy with me, and I was happy with myself too.

But, as they went through the bag, as they talked about how they might use the various things I’d retrieved, I kept thinking, remembering, the boy. I could hear that strange off-key tune he was humming. I felt I could almost picture him at that table, doodling on that piece of paper, and I sank into a strangeness and wiped my eyes.

The man in the tall hat looked at me, and he placed a hand on my shoulder. He seemed to understand something, though he held it back. I told him and the woman I was fine, and when I felt calm I shed the coats I had brought and looked around.

—Where are the brothers? I asked.

What?

—The bearded brothers, where are they?

That’s when the man in the tall hat went pale.

And he no longer seemed as happy with what we’d done.

• • •

We sat around the electric lantern, and, in a hushed voice, I explained in detail what I noticed when I returned, everything that had changed from what I remembered before. The green color of the stars that I believed had once been red, the straightness of the street which had once curved one way and then another, the floating movement in the sky that may have been some winged thing from another world. And, of course, the bearded brothers who apparently were no longer with the man and woman in our house.

There are no brothers, the man in the tall hat said. And there were never any brothers, because of us.

I didn’t understand.

We are not the same house that you left. You’ve come back to the wrong place. Or you are not the same person we sent to the Liar, and he went back to the wrong place, the man murmured. This was the risk. Always the risk, of any changes, consequences. I’d hoped it wouldn’t be, if we trained you. But it will always be the case. I’d been sure. I was sure. Or almost. Almost sure, I suppose.

It was probably the wrong thing to do, the thing I said next. But I kept thinking of the boy, sitting at that table, drawing and humming that strange tune, and I could not get that out of my head.

—If there’s nothing good here, what does it matter if any of it’s changed? I asked.

The man in the tall hat looked at me. He was not touching me, but it felt like he was grabbing me by the shoulders and pressing me into one spot, with just that look.

I imagine it would have mattered to those brothers, he said.

I thought about the Liar and the houses, what she had told me earlier about four walls and doors and windows, and inside and out, how the separation between things was more illusory than real. I thought about how the brothers might still be there, in some other place, if we were to look for them. How other things might still be somewhere, if we looked for them too.

—When I was out there, traveling, in the other houses, I said softly. There was someone, a boy. He seemed somehow to know me, and I think I may have known him. And this little boy …

Stop.

The man in the tall hat shook his head.

But the woman with the scarred cheeks leaned in, listening carefully. She had an unusual faraway expression like she was remembering something that had nothing to do with me.

—I just think … even with any changes … I would just rather look for the possibility of the new than the certainty of this. That’s all I am trying to tell you.

If the man in the tall hat understood that time, he didn’t want to hear it. He stormed out of the living room, and the woman chased after him. They left me by myself near the lantern, and I waited for some time, before I leaned over on my side, and eventually slept there on the floor.

In my dreams, I thought I saw two white shapes walking in the halls of the last house—flickering here and there, together, standing over me quietly and watching me sleep.

• • •

After that, the man and the woman drank heavily together.

They poured the two bowls and spoke in low voices, facing one another for some time. This was some old disagreement between them that went beyond my understanding. Something I said had stirred it from their depths. I watched from the other room, where I sat by the lantern, trying to listen, but they may as well have been speaking another language.

At the window, I looked up at the green stars, the clouds, and saw that flying thing, now and again. But I found it slightly less frightening when I glimpsed it, because it reminded me of that other place, where the boy had been. An odd reminder of something that held my interest rather than frightening me. And I could almost hear it again, that strange off-key tune that the boy was humming, coming back to my mind.

Then one night, I woke next to the lantern, and the scarred woman was leaning over me.

Did you mean what you said?

I was uncertain what she meant, specifically, but looking in her eyes, I think I knew.

—Yes.

Even if there are problems. You accept. You’re sure?

—Yes. I am sure.

You would take a next step. Whatever it is. Over what you’ve been given?

—Yes. I am sure.

She held out her hand and looked at the sheath-holster. I knew she was asking for the knife. It occurred to me that she could have taken it from me while I slept, but she did not, because the knife was a sign of trust. Our trust, in this knife.

And within that, the scarred woman gave me a choice, maybe my first choice of anything I can remember here. A decision that held a promise, from me, that I would bear certain consequences.

I had thought about this, in some way, already, while the man in the tall hat and the scarred woman had been drinking, when I spent time over in this part of the house, considering. The place, here, the neighborhood. There was no such thing as a clean moment or perfectly empty state, no wiping the mind into absolutely nothing, though they had tried. Everything, these last houses, birthed from other moments before. And not going back to the Liar was, in a way, its own choosing, of those preceding moments that had nothing to do with me.

And that was not the choice I wanted, and I knew it was not what the scarred woman wanted either. So I gave it over, the knife, and she nodded and told me to take the duffel bag and everything it contained.

When I close the doors to the den, you must leave. Don’t stop. Don’t stay. Don’t look. Just go. Okay?

—Okay.

Okay?

—Okay.

On your way with you.

—On my way with me, I replied.

She wrapped her cold hands around my face and kissed my forehead.

• • •

Outside, it was brighter, under the green-tinged stars.

I could hear from the street, yelling, inside the house. Heavy thumping, all kinds of noises. There was also movement around the other houses, those white flickering things, gathering like a crowd, their heads larger and more flowery than the last time I’d seen them.

Some of the figures began walking slowly toward me, something else I had not seen them do before. Their arms dragged along the sidewalk, and their heads twisted in my direction.

I reached absently for the sheath-holster before remembering it was gone.

I was nervous, ready to run for the cul-de-sac, just as I had been told. But from the house behind me, where there had been so much tumult, came something worse. An immediate stillness. So I went back through the front yard and the curling fog up to the windowpanes and peered into the room, quickly.

The scarred woman’s body lay on the dark, slick floor of the den. Across from her, the man in the tall hat sat against a wall, clutching at his bloody stomach, his eyes fixed on me in the window. Every inhale and exhale, sharp, his expression so accusatory—then so frozen, I could not tell if he was blinking or breathing at all.

Between his stained fingers, in the gash in his belly, something moved.

A third hand, and then a fourth, reached out of his stomach, long arms braced against the floor, as something pulled itself out of his body. I did not stay for more than another second, but in that brief moment, it looked like another—another man in a tall hat, coming out of the one before.

I hurried down the straightened street, trying not to look back or at any of the white forms across the road. The pale, floating shape in the sky flickered in and out above my head, like it was watching me go, all the way down and back to the angular houses and the cul-de-sac.

The Liar did not seem wholly surprised to see me again.

I handed her several bottles of whiskey, looking at the street behind me, while she poured the bowls. We drank the customary first drink, just as we did last time. Her eyes were tired.

You can’t undo what’s done.

—Yes.

There are only things you do after.

—Yes.

Be careful of fixating. One form, one house, one world, one person. Attachment is like an infection. And these are just representations, after all.

—Like an infection.

I did not have the presence of mind to fully answer the Liar, just then, but something about that seemed wrong to me. Partial and incomplete. Like an omission that she perhaps didn’t even fully perceive. Forms could matter, sometimes, to us, I thought. The more we fixated, the more we attached, the more meaning we could draw. The deeper we could sometimes go. But I did not have the time to say any of those things to her.

Nonetheless, the Liar seemed to know. Her expression was incredulous, as though she didn’t believe in such matters. But it also seemed like she didn’t know enough to disagree.

However you go about it, you won’t be alone.

—What?

You can’t undo what’s done.

She pointed a soot-covered finger, and I could see, in the distance, the silhouette of a man in a tall hat. He walked leisurely along the sidewalk toward us, like some casual ruin intent on approach. I grabbed the duffel bag in a panic and wondered if I might make it to one of the houses before it reached the cul-de-sac.

Remember, these are only representations. They are not—

But if the Liar had anything else meaningful to impart, I did not hear her. I grabbed my bag and ran to the houses, none of them exactly the same as they were before, or ever would be again, I knew.

I opened the front door with the iron knocker and dried wreath. I could see the shape of that man in the tall hat coming closer, almost at the cul-de-sac now, when I shut and locked the door.

I waited and held my breath and pressed my body against the wood. Behind me, I heard that light, offkey tune—a voice, humming, almost substantiating itself in seconds from somewhere beyond. And I felt that chill in my stomach, and the tears coming back to my eyes when I heard the boy, again.

I would turn, I would go to the other room, in just a moment, once I was sure that nothing would come through behind me. To that boy who had been waiting for me, maybe longer than I knew. Seconds, then minutes. Nothing came for me just then. Nothing. A little longer, and then, like I promised, I would go.

As soon as I was sure—nothing of those changes and consequences, coming.

When I was sure, I would go.

As soon as I was sure of it—nothing.

When I was sure, I would go.

Almost sure, yes.

Almost sure, I would go.

Copyright © 2024 by Thomas Ha