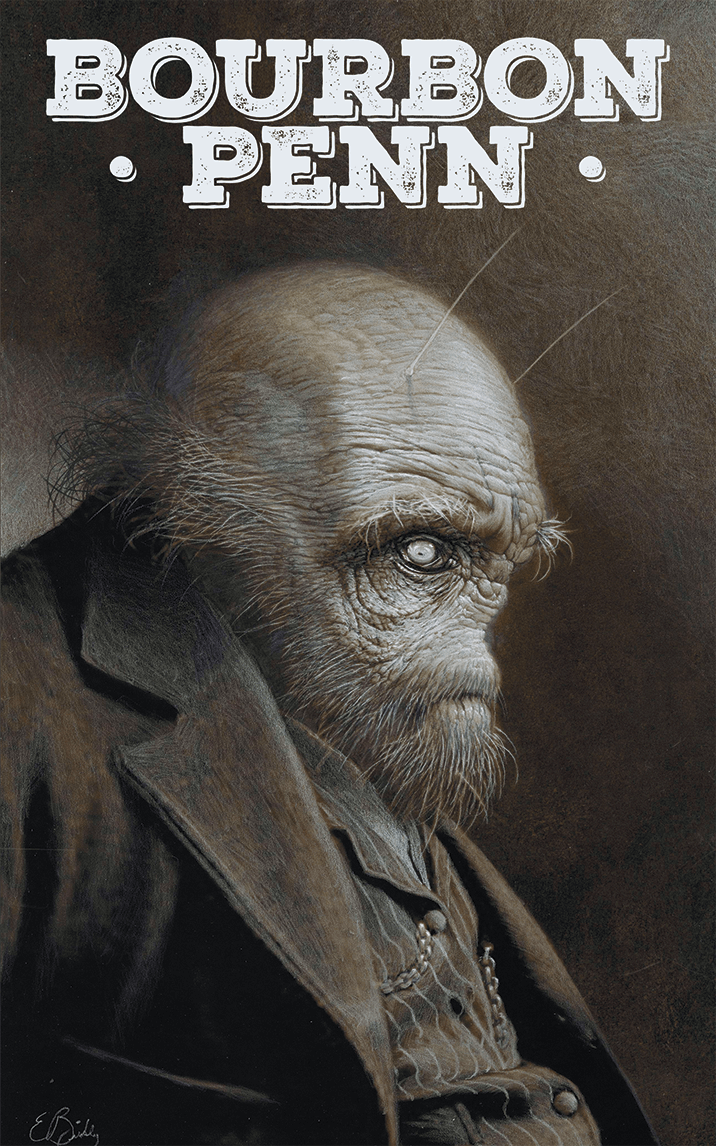

Black Hole Elvis

by Nikita Andester

The first time mama and I did shrooms together, we were listening to Elvis. If there was ever a mascot for the hell crater of the west that is Vegas, then his warbling ghost would be it. Trust me, I’d know. The last time mama and I did shrooms together, we met the guy.

But I’ll get to that. We started off here, power walking around Lone Mountain, which was more an overstated hill than anything else, slouching outside our apartment complex. Mama’s body glinted like a penny in the sun, and her hands moved almost faster than her spindly legs did. “The crazy thing, Syd, and I mean the craziest thing about it? I feel totally fine. Abso-fucking-lutely normal.” She punctuated each syllable with her hands. Sweating as I raced to match her pace, I had to agree.

“Normal,” she continued, not waiting for me to respond. “I mean, you read about it, fucking cancer, on Facebook or Women’s Health in the waiting room at the dentist, and you think how terrible it must be before turning right around and thanking the lord it’ll never happen to you. But I guess sometimes it just goddamn does.”

We’d had this conversation what felt like a million times over the phone already, but this was my first time watching her say it in hummingbird motion. It was only my second day in the city since Tarrick and I had packed up the lives we’d spent a decade forging in L.A. to upend ourselves in the apartment across from hers. Consoling her felt so much more feeble in person. After starting and stopping a few times, I tried the positive tack. “You’re so strong, mama – there’s so much hope –”

Mama was hardly listening. For all the good it would’ve done, I could’ve pointed, shouting, “Look, mama! Sydney Poitier is doing backflips down the mountain!” She was addicted to Turner Classic Movies, so she’d have loved that, if she’d been listening at all. She wasn’t.

“Me? Dying? I don’t buy it. Between you and me, I’m gonna prove Doctor Whosit wrong. There’s another decade left in these old bones. Maybe even two. I love my job too much, the lights, the cards, the sound of the slots. Love it. You know how bad I wanted to move out of Mobile and get out here. Past few years have been a dream, an absolute dream, and Doctor Whatshisname—”

“Doctor Quinnell.”

“Right, Doctor Quintrell. He’s going to feel dumber’n a pig after he sees how many more years of dealing blackjack I’ve got left under this belt.” She tapped her waist (which, for the record, had no belt) and strode ahead, ignoring the sweat trickling off my temples. This chub rub was killing me. I’d thought L.A. had been rough in the summer, but it had nothing on this swelter. And now I couldn’t even toil in traffic for an hour to go dip my toes in the water in Santa Monica. Jesus Christ, August was the worst month to move.

“Between the radiation and those god-forsaken green juices you came all the way out here to force feed me, I’m living forever. It’s just that Doctor Whatsit …”

The entire circuit around the tiny mountain went on like that, me nodding, wanting to reach out and rub her back but too afraid to, on and on until we were all the way back at the lava rocks between our apartment buildings. “Get Tarrick. I need to give y’all a tour of the grounds. Don’t want to get lost out there.”

“We took a tour when we visited a few months back, mama.”

“Still could get lost.”

“We won’t get lost.”

“Get Tarrick.”

I texted him. God, my feet were killing me. The rocks clicked under my shoes as I danced from one foot to the other.

“You tired after that walk?”

“I’m fine.” I wasn’t.

“Feet don’t hurt?”

Of course they did. “No, feeling great.”

“You sure?”

Tarrick popped his head out the door, saving me from answering.

“Well, come on then!” Mama flapped her arms like a plucked chicken. “We don’t have all day, you know.” By the time Tarrick had slipped on his shoes to join us, mama had already started marching ahead. The tour was long, arid. Mama was so thorough I swore any minute she’d start defining the words. Now here’s the pool. A pool, you see, is a manmade body of chlorinated water …

“Here’s the pool.” She dragged us right up to the gate to look in, no nevermind you could see it from our balcony. “Jacuzzi, too.”

Tarrick, like always, had infinitely more patience for her than I ever could. “Nice, Kittie, love it. Syd, maybe we can check it out tonight, huh?”

His kindness was lost on her. She scuttled ahead, Tarrick’s palm finding my own as we rounded the corner, stretching our strides to keep up with the tiny woman in front of us. “The mailboxes,” she gestured and we nodded, just like people on a museum tour. “You can use your key –” holding her own up between us, she then slid it into her lock, struggling with it for a second before it gave, “– just like that.”

“Just like that,” Tarrick said.

She smiled at him and kept walking around another bend, bringing us to a door she pushed open. “The gym. Here, Tarrick, look. A treadmill, and one of those machines – what’s it called? – a Bowflex. Some weights too, for all that lifting you do.”

He kissed my temple. “We can lift together, huh?”

“Oh, please. Syd could barely lift Bodie.”

Hugging myself, I pinched at the flesh of my upper arms. Bodie was the closest thing to a child Tarrick and I ever planned on having, and out of the three of us, he was taking the move the hardest. The poor guy’s Himalayan fur was in clumps all around the carpet, and he’d started gnawing on the corners of the couch whenever we left, all panic and saliva and frayed pleather in what I imagined as a strange protest of one. My arms were red and dimpled under my hands.

Tarrick rubbed my back just as mama rushed us off toward, yet again, the recycle bins, taking us on one final loop before circling back to our apartments and dropping us at our front door. Inside, the fan tried and failed to lift the hairs plastered to the back of my neck. Tarrick gathered Bodie up in his arms. “You can so lift Bodie, firefly.”

Foisting the wilting cat into my arms, he kissed me again. I buried my face in what was left of Bodie’s fur as Tarrick passed between the half wall separating the kitchen and living room, disappearing behind the fridge. The freezer door whispered as it opened, then smacked its lips back shut.

“I know one thing that’ll cheer you up.”

“A beer?”

“Better. This.”

His arm shot out over the kitchen sink, right into the middle of the half wall’s frame, dangling one of the baggies of shrooms we’d bought before our move. Something between arousal and alarm shot from my root up to my throat. Daylight whispered against our carpet, illuminating dust motes dancing over boxes. Mama’s apartment spied on us through the balcony’s sliding glass door. Tarrick followed my gaze.

“Hey, come on. We gotta be able to live our lives. I agreed to move here as long as you,” he pointed at me with the shroom baggie, “promised we wouldn’t turn into skulking teenagers.” His tone softened. “Shit’s hard right now. You deserve to unwind. Set the right tone, you know, position yourself mentally for the duration, for however long – however long we’re here. But,” he began retracting the baggie, “I don’t wanna pressure you, either.”

“Wait – you’re right. Let’s do it.”

“Sure I’m not pressuring you? We don’t have to do anything you don’t want.”

“No. No, it’ll set the tone. Clear my head. Let’s go.”

Tarrick upended the baggie onto the cutting board, muttering, “Only if you’re sure.”

Instead of answering, I let Bodie leap from my arms and pout on his chewed couch arm, joining Tarrick in the kitchen to rifle through boxes ‘til we found the butcher’s block. After cutting the suckers up just enough to chew, Tarrick and I faced each other, performing the most sacred step of all: turning off our phones.

After I alternated between swallowing the pieces down and flooding the dregs from my molars with cheekfuls of water, there was nothing to do but wait for the tide to pull us out to the hallucinogenic Pacific. We unpacked a box in the living room: photo albums on the bookshelf, a spindly row of tomes from separate childhoods that eventually blurred into our first shared one with a zebra print cover, RiteAid price tag still on it and everything. Mostly the photos were from our early drag performances, including the one we met at, back at Tulane. Spanish moss hulked over a bar just off Frenchman, creeping in on the two of us standing together, somewhere between too close together and too far apart. Me in my Dollar Store Elvis act, and Tarrick towering over me in high heels and his papier mâché alien headpiece, the highlight on his cheekbones blinding from the camera’s flash.

“I love you.”

“Mm, I love you, too.”

Nausea curled around us soon after. We collapsed under its riptide, surrendering to that cosmic sea. I vibrated louder and louder, until the colors and cities of the whole wide map of the world turned soft, but somehow harsh at the same time, like we were clownfish in an anemone bed. I swear, there’s nobody I love more than Tarrick when we’re on shrooms. I mean, obviously, when we’re not on shrooms, I still love him more than I love anyone else in the whole damn world, but when we’re rollicking on that crest, the space of light brown in his eyes yields to a madness, the mayhem of everything good, a chaotic good, and when I see all that bursting under there like a blossom of activating yeast, that’s the moment I love him with the fervor of an initiate worshipping their cult leader. Yeah, that’s exactly the tint his eyes take when we’re shrooming. The color of a cult leader, promising me the latest plane of existence, and when I see all that nestled inside him, I get all buried in the canyons surrounding Vegas or caught in the heart of a forest fire that crawls its way over tree after tree, a drowning person pulling herself onto a dock.

Eyes locked on his, we swayed. He touched my hair, which suddenly felt as thick as soup. Mostly, we were silent. Sometimes, one of us said “wow,” and the other answered, “Oh, firefly,” until we were prostrate on our knees, worshipping each other, and now I was the cult leader, my capillaries glowing with the power I wielded, thankful for my own benevolence. The sparrows in my throat were emerging to sing, and when I glanced at the bedroom door it shone with gold, good lord – this was our oasis. The kitchen smiled at me through the half-wall, cabinets grinning on our union, the union of me and Tarrick, a squid and a ship, a tiger and their queen, two aliens humming through the void –

The door barked. Somebody. There was somebody outside. I held my breath so they couldn’t feel me moving the walls in and out.

Another knock. “Baby? It’s just me.”

Mama. Who the hell else could it have been? Shit. The maw opening to the kitchen was laughing at us now, the walls biting and clear, everything mottled in the gray of time. My face was doughy; Tarrick’s eyes were wilting.

Until they brightened. “Hey, Kittie. Hi.” Tarrick, my angel Tarrick, raised his eyebrows all the way up to his hairline. Now I’m no mind reader, but I felt sure he was signaling for me to play it cool, so I did.

“I tried calling y’all but your phones were off. So I thought – well damn, I’ll just head on over and, here, why am I talking through the door? How about I just come in.”

Before my mouth could form a protest, she opened the door, bringing daylight and a gust of the outside into my eyes. The heat rushed, visible, tickling the air conditioning til it chortled.

“Mom, wait—”

“Kittie, I—”

Too late. She saw us kneeling on the floor. “What’re you doing down there? Unpacking? Anyway, my vacuum’s broken, and I was wondering if I could borrow yours. Y’all do have one, don’t you?” Her face moved like she was underwater, and I realized I’d been swaying. “Y’all okay?”

“Yeah, we’re. I’m. It’s—”

Tarrick stood then, proud as a warrior. I could practically see the tattoos on his chest, the battle scars marking his arms. His chin high, my lord was he gorgeous, he spoke the word of God. “Kittie, you’re wonderful, and we love you, and,” I nodded up at him, smiling, “and we’re on shrooms right now.”

She stared at us for a minute or maybe a decade, ‘til her wrinkles took on the sheen of laminate copy atop a moving photograph of her back when she’d been my mother, although of course she was still mama, but I mean when I was a baby. She was so beautiful in the doorway, a halo of light blaring in from outside, crowning her hair of straw all magical, looking as if she’d live forever, and I was so certain of that I just had to laugh, and when I did, she kept standing there, making me nervous. I stopped laughing, the silence stretching all taffy-like. Finally, she spoke. “I’ll come back when you’re done.”

She twisted the knob as she shut the door, leaving us with hardly a sound. Our trip wasn’t the same after that. Her presence pricked the back of my mind, blood welling in the needle marks of her absence, her presence, her absence, her inevitable death click-ticking toward me. She didn’t seem so immortal now that I couldn’t see her laminated face. Coming down, Tarrick held me on the carpet, which was scratchy in a pleasant sort of way. Bodie purred on the couch beside us, relieved we were acting normal again.

Tarrick sighed. “You think he loves us as much as we love him?”

His question consumed us ‘til we came down all the way. Tarrick and I split a soda water, kissing it and then each other before settling in for bed. But try as I might, I couldn’t scrub mama from my mind, her face undulating behind my eyes until sleep finally swallowed me whole.

In the morning, she came over for the veggie juice and coffee we’d agreed on the day before like nothing had happened, the only difference being that she actually waited for us to open the door after knocking.

Taking such a small sip of juice I swear to God it was some kind of performance art, she looked us both square in our eyes, somehow at the same time. “I Googled it, you know. What you two were up to last night. Drugs. Magic mushrooms.” She whispered those last two words even though we were alone at my own dining table. “Anyway, I’m not mad at you. Just. Be careful. Lord knows I smoked pot as a kiddo. Don’t get caught though, okay? And don’t do anything that would get me arrested.”

It took her ten more minutes after that to finish her juice. The whole time she winced, blowing air out of her nose the same way most of us do after drinking room temperature Evan Williams. The last sip, she coughed a little, then stood. “I need to go start my day. Thanks for this. It was tolerable.”

Later, when mama and I lounged by the pool, she peeked at me over her sunglasses. “God I’d kill for a drink.” Mama hadn’t had a drop since the diagnosis. “A beer on this hot-ass day? Syd, I’m dying here – literally.”

“That’s why you’re not drinking, mama, right?”

“Fuck, I guess.”

She was quiet for a while before slipping into the pool, swimming from one end to the other, then back again. Plopping in beside mama, who was elusive as a minnow, I felt about as graceful as Bodie. We lapped a few times then met at the deep end, resting our arms against the hot lip of the pool and pedaling our legs under the water.

Her mascara had run. “I want to try it.”

“Drinking?”

“Don’t be obtuse, Syd. The magic mushrooms. I want to try it.” I was silent for a half-beat too long. “Well? You gonna say anything?”

Her posture, bottom half submerged, was a catalog copy of casual. Every muscle strained to look at ease. “Yes, mama. Yeah. Absolutely. Let’s do it. When?”

Waving the question away, she sank back under the water, swimming until she was a mirage at the other end. I dunked my head and returned to the laps, too. We didn’t synchronize once.

Two weeks later, mama and I stood in her living room as the sun sank behind her building. Half bouncing on the balls of her feet, she glanced around. “This it?” She fiddled with the lights, turning the end table lamp on, the overhead off. Overhead back on, end table lamp off. “What kind of lights do these things need.”

“They don’t particularly need any kind of light, mama.”

I said that from the kitchen, where I was busy pulverizing mushrooms in the coffee grinder I’d brought over from my place, whose layout was a carbon copy of hers. Scraping each fleck of shrooms tucked under the blades, I stirred what looked like even amounts of powder into two cups of Tropicana. The powder tinted it only a shade different, like sad orange juice. Mama squinted, her eyes inches from the glass. “You sure there’s enough in there? I don’t see anything. Should I see something?”

“It’s a powder, mama. You don’t want to see anything. Just drink it up like you would a green juice.”

“You and those godforsaken green juices.”

“They help you.”

“I know, honey. I know.” She made herself smile. “Thanks.” Saluting me, she started glugging it down. I followed.

Those first ten minutes of waiting were agony. Mama kept sitting on the couch, then standing up again. Drumming her hands. “Let’s put some music on, huh? I got ants in my pants. You ever get duds? Maybe these are duds.”

“These are good, promise. Same ones I took a few weeks ago. As for music, I know a perfect—”

“I want Elvis.”

What could I say? It was a dying woman’s request. Shrugging, I pulled him up on my phone. His voice trembled from the speaker. Wise men say …

She stilled under the touch of his words. “That’s the stuff.”

We were quiet. Then. “Should I be feeling nauseous? I’m feeling nauseous.”

“Here we go.”

Since her apartment mirrored mine, it was easy to feel like I was home, even though I wasn’t. Warmth pulsed straight through my body, down to the knuckles, and mama’s electricity hummed through the length of her and looped into me, in and out like an accordion of us that started harmonizing with a memory:

Mama, helping me get ready for my first high school dance. I was thirteen, fourteen. She had hairspray in one hand and a curling iron in the other. “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone” by Paula Cole had just started and she (mama, not Paula Cole) shook the can in time with the beginning. Her mission was to flip my bob, you know, like Drew Barrymore. Not that it mattered. Nobody had invited me to the dance, but was it any surprise? The dress might’ve technically fit, but I still looked like a Twinkie wrapped in satin.

The flip held. She gave my bangs a poof and another spray. Just as the song reached its breakdown, Paula yelling, “I am wearing my new dress tonight,” mama cut through the music, her eyes scraping me raw like she were gravel in my shins – and, mind you, while I saw all this, I also saw the living room floor, saw mama, much older and wrinkled, sitting just like Yoda, eyes closed and vibrating and falling and shaking, and was this her living room or mine? I couldn’t tell, but as clear as if it were happening in front of me, Young Mama stepped back from my hair and pursed her burgundy lips before saying, “You look cute. The hair helps hide how fat your face is.”

At the dance, I’d cried in the bathroom, hating myself, hating my fat stupid face, wondering why I’d come. Nobody had wanted to dance with the Twinkie, and anywho my only crush back then had been Leah, and lord knows you didn’t dance with other girls in Mobile in ‘97, and so I’d sulked by the punch, downing a third cup, then hating myself for drinking that third cup, pinching my arm fat as if brute force could make it disappear, praying for mama’s wiry self-discipline, and suddenly, my eyes in the present, in my living room over twenty years later – no, wait, her living room – she smiled at me bright as the eclipse, one laugh hiccuping out her throat.

“Remember the dance I went to in high school? Freshman year? The one that was beach themed?”

“Oh, that one! Mm, I can see it now. So sweet. Remember we spent days hunting for the right dress?”

Her eyes, at least when they weren’t trembling in her face like dumplings floating in gravy, were shroom-clear, relaxed. Weren’t we gliding on the same length of typewriter ribbon right now? She’d get it. She knew my feelings as clearly as I felt them. How could she not?

“I forgive you, mama. For making me feel so rotten.”

Her open moonrise face didn’t change. “Oh, I don’t remember, honey.”

“You called my face fat. You did that a lot, I guess.” I said it as casually as if I were suggesting we watch a movie later.

She laughed in a way that made me feel sure she loved me. “I was just saying a fact. It was – in such a cute way. Those cheeks, so, so” she leaned toward me and pinched the air around my face, pulling at those invisible cheeks like they were bubblegum. She dropped her hands. “I did that a lot back then. Sometimes, oh sometimes, being a mother means wanting the best for your baby so bad that you’ll do anything – and I mean anything – to make them strong. Even if that means ripping them in two. You’ll understand one day when you’re a mother.”

When you shroom, there’s still the smallest sober voice in there. Most of the time, it’s more of an observer than anything else. But right then, that inner me was shaking. It wanted to scream that I’d never be a mom, that she didn’t know me, that “motherhood” was a word that wouldn’t ever fit around my shoulders for a hundred thousand different reasons, that I basked in partnering hairy legs with lingerie, that I once lived for drag king nights I gave up for her, my god, did she know how much I gave up for her? Being as rotten of a mother as she’d been wasn’t on my to-do list, not now and not ever.

I didn’t say any of that. The trails my fingers made in the air took my focus, and I let the memory fall from my grip. Just like that, I adored mama all over again. We had Elvis; at least there was that. Sitting on the floor, his crooning cradled us both, and every once in a while we’d look up and around, meeting each other’s eyes, and I swear she loved me too right then. When it was over, I wanted to hug her, and I think she kind of wanted to hug me too, but we didn’t do that much back then, even though she was dying. She patted my shoulder.

“I love you, mama.”

“You know I love you too, honey.”

The next morning, mama stood in our kitchen, hands on her hips, staring down the veggie haul Tarrick and I had just brought home from the grocery.

“Y’all juice all this in a week?”

“Yes ma’am, we do.”

Mama’s raised eyebrows directed right at my belly implied something I had no intention of hearing. “Guess y’all split it with me, huh, so it isn’t quite so much as it looks like.”

Tarrick had a menu. He always did those days, and as the only body-positive, queer nutritionist I’d ever met, I trusted his wisdom. He’d make soup and touch my soft thigh and say, “This’ll make you live forever, firefly.” And since I’d gone and marooned us in this desert far from L.A., the menus had become his Eucharist. Juices for us and mama, and then treats for just us two, the happy couple making sushi behind a locked door, shielded from the desert winds of a dying mother. I don’t know. Maybe the shrooms were talking.

The first juice we’d made her, she’d gagged it down, shaking her hands at the wrists as if she were fixing to speak in tongues, shouting, “Christ, I’d rather die. Bring me a beer and my deathbed, instead.”

But now it’d been nearly three weeks; she was used to it. Mostly. Tarrick had gone and added an apple the past week, so now although she still gagged like we’d forced her head under a bowl of green juice in a hazing ritual from a health nut frat house, she didn’t start rattling off in tongues. When she drank this one today, she even smacked her lips. “That wasn’t half bad.”

“Mama, you sounded like you were dying.”

“Please, honey, I was just giving some emphasis,” She said each syllable like a separate word, em fah sis, “to let you know I’m still not appreciating this whole damn thing.”

Mama was a terrible liar. Tarrick glanced at me with a twitch of his brow; he knew sure as I did that she was lapping this attention up. The foam from the juice lingered round the rim of her cup, and we sat at the table, the living room mostly unpacked. Tarrick ran his finger through a drop of juice that languished on the tempered glass.

“So when can we do it again? The magic mushrooms?”

Mama’s question took us both by surprise. Tarrick laughed, his mouth lighting up the whole sky, and I laughed too. After a heartbeat, mama joined in. It only took a week and a half before we were at it again, Tarrick, me, and mama sitting on our back patio with paints, paper, and an armful of fabrics piled between us – scraps from our unfinished projects. Bodie washed his paws, annoyed with all three of us as we cooed at sequins and fondled the poured concrete floor.

Somehow, I managed to lay a big piece of paper between the three of us, so white I had to squint, and then my fist clenched a tube of paint, squishing cornflower blue straight onto the paper. I’d expected mama to hesitate, but she surprised me, painting with her fingers, her hands like swollen-knuckled crabs scrabbling across the ocean. When I leaned in close enough, I could practically smell the salt in the air, although sometimes it just smelled like acetone, since Tarrick was alternating between painting his broad big toe and using the crimson nail polish to add seagulls to the page.

Elvis was on again, the whole Blue Hawaii album this time. My hands were each a small Elvis, tilting his hips along the shore, singing you are heaven to me, about to meet a honey in the sand, when mama’s voice lassoed me off the painted beach and dumped me back onto the patio.

“Sometimes, I feel like a version of my mother. Like someone had, had scored paper to cut the shape of her out, but I got caught underneath. Know what I mean? Like she was an image of sharks, and maybe I’m oil rigs or a pool hall. Stretching out, and out, and out.”

Tarrick nodded, solemn. “I feel that.”

My pulse turned all Play-Doh. She never talked about her mother. And when she did, it was only by first name. My Elvis hands sat in my lap, poised to listen. “Once, Mallorie,” there it was, her mother’s name,“kept me from seeing someone. A boy. I liked him, about as much as you like anyone at sixteen. One time I came home late after kissing him some after school. Somehow she knew.” Tarrick and I hardly breathed while mama paused, gathering her breath. “Scrubbed my face so hard I bled. I was red raw around my mouth for weeks.” She dabbed some paint around the paper. “Anywho, I only bring it up because we’d first kissed while listening to this record together. It always makes me think of him. Peter Garvey was his name. Stopped kissing me after that, I guess because he felt guilty. Going to school with my face like that was something awful, let me tell you.”

Mama’s story ran through me, and I rubbed at my own face to feel her chapped ring of the past around my mouth of the present, sure then I was exactly like what mama had said about her own mother, a paper cutout copy, mother after child after mother after child. The paint on my hands trailed a goatee around my face, and both mama and Tarrick laughed. Crawling over to face me, Tarrick kissed my forehead, digging his knee into our artwork, his toenails still only half finished on the left foot. He squelched emerald paint onto his fingers right out the tube and started adding to my beard, losing himself in the rock slab of my face.

His eyes were that crystal mayhem again, the color of glee, and sunlight shone through the ends of his tight coils, turning him into a saint. Patron Saint of Beards, maybe. I couldn’t see what he was painting, but I was sure I looked beautiful. Mama watched her hands, then me, then her hands again.

“This is me. My truest self, mama.”

My favorite skirt, thick with pleats and pictures of teapots, pooled around me, and I could practically see my new beard, so thick and soft, almost to my shoulders and the deepest green in all of Vegas. Tarrick kissed my cheekbone, just above the paint.

For once, mama was warm, like the mom she maybe wanted to be in secret. “The truest you? Then I’m all for it!” She spread her arms wide ‘til her wingspan could practically envelop the whole patio.

There’d never been a more perfect day. We returned to earth tender at the edges. Somehow, two months passed like this, us all tripping every ten days or so. Pills, juices, radiation, repeat. Mama was dead set against chemo, and I didn’t blame her. If she only had six months to live – now less than three, oh God – then she’d spend it nimble. The shrooms were helping, at least in the sense that she seemed happier. Even Tarrick started seeing the shrooms we bought from the family down the block as some secret talisman for eternal life. Mama adored him, more and more each day. Sometimes I resented it.

To mama, Tarrick was fit and interesting, better equipped to keep her happy than her miserable flesh-and-blood. Tarrick, the juicer. Tarrick, the nutritionist. What could a remote accountant do to compete with that? No nevermind I made her juice as often as he did. But at the end of the night, always, I loved him too much to get mad, especially since he’d taken to holding me in the shower as my grief about mama spooled down the drain. Three months left was nothing. I was just so mad at her. She was dying. Why waste her dwindling time doing calculations complex enough to land us on Mars, all to find out how a dumpling like me landed such a spouse?

Even dying, mama was exhausting. This morning especially. It was the first cold day of the season, and we were standing outside waiting for someone to call our table at this brunch spot just a few blocks away from Circus Circus on the Strip. Lately, mama had been feeling it – the whole dying thing. But today had been a good day, and after our juice (which she’d barely choked on) and some ibuprofen, she’d been good enough to go out, have some brunch, hit the blackjack table to shmooze. She wasn’t dealing cards anymore; hadn’t for the past two weeks.

So there we stood outside, perusing the menu in Tarrick’s hand, me holding a cup of coffee, Vegas cold and drizzling in a way you never see in the movies. Waffle sandwiches, vegan steak ‘n’ eggs, breakfast burritos, French toast. Lord, I was hungry. My nail quivered above the words “fizzy cherry float.”

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you. This move’s already made you fat enough.”

A teenager from a family waiting outside glanced our way and I wanted to die of embarrassment. When a teenager pities you, you know you’ve sunk low.

Tarrick touched my arm. “Syd and I moved here to help you. They’re fine the way they are – and they’re doing enough.”

“I’m just saying it for her own good, I mean, come on,” she poked my belly, which felt white-hot with hate.

I never thought I’d see it, but Tarrick finally lost his temper with her. “Are you seriously fucking doing this, Kittie?”

But before he could say another thing, the words flew out of me, my jaw tight enough to compensate for all my jiggle she just couldn’t stand. “I’m giving less and less of a shit about what you think. Clearly your fear of fat hasn’t gotten you shit. You’re still – god damnit mama, you’re still dying like the rest of us.”

Now two whole families were watching us as we all stood under the strip mall’s miserable eave. Come one, come all! Skip the Strip – witness two former drag performers duke it out with a dying woman, all before BRUNCH is over! Mimosas, two-for-one.

Her mouth opened, then closed, and right as she turned heel and stalked toward the car, a tiny server popped their shaved head out the door. “Kittie, party of three.”

Squeezing my hand, Tarrick turned away from mama and said, “Right here.”

The families craned their heads after us, and I carried myself like The King as we walked in. The server read our tension, topping off our coffee cups before leaving us be. Through the blinds, mama’s slouched frame nearly disintegrated. Only her khaki jacket kept her white button-down and blonde hair from disappearing into the hatchback and overcast sky. My anger trickled out of me, down into the vinyl seat.

“I’m sorry, firefly. You know you’re healthy as they come.” Tarrick squeezed my hand and I kissed his knuckles, blinking hard.

“How’s she still so goddamn mean?”

“Wish I knew.”

Too soon, mama walked through the doorway, heading for our table. I barely muttered “Jesus” under my breath before she stood at the head of the table, shoulders slumped.

“I’m a rotten mother.”

Whatever I’d assumed she’d say, it hadn’t been that. Tarrick squeezed my hand and leaned back in what was his best disappearing act. “Mama, no.” I sighed. Of course she was a rotten mother. But she was a dying one, too. “You – shit – you’re mean sometimes. And others you’re playing the martyr, but,” I groped for words. “You do your best, like all of us.”

“Don’t placate me, you know I hate that.” She sank into the chair and took a sip of my coffee anyway. “I could’ve done better. Accepted you, all of you, even that belly.” Ignoring my face, she turned to Tarrick. “I’m a rotten mother, aren’t I?”

“I, Kittie,” He took a breath. “So be better then.”

Nodding, mama took another sip of my coffee. “Be better.”

“Mhm.”

How’d he always know what to say? The question nibbled at my tofu scramble and sipped at the cherry fizz float, which wasn’t even that good. I’d only gotten it to prove I didn’t give a shit what mama thought. We didn’t say much, but once, she did lean across the table to squeeze my hand, releasing it quickly as she’d grasped it. It was something. Still, Tarrick talking to mama so much better than I could swirled in my head til well after brunch, mingling with the cigarette smoke we waded through at Circus Circus while mama visited her old friends. How could someone like her have friends? On the drive home, I tried to think of normal things to talk about, couldn’t. Elvis came on the radio, saving me from saying yet another inane thing about Bodie. “Suspicious Minds” wove through the car. In the passenger seat, mama stared out the window.

The tension lingered a few days later, when mama and I sat on her living room floor, shrooming again. For some reason, she’d suggested doing it just the two of us. She usually always wanted Tarrick to join. Said he was more fun. Her picking me humbled me, and I still rode on that warmth while we waited to float away.

“Baby, I’m scared.”

“Of shrooms?”

“No, of dying.”

“Oh. Me too, mama. About you.”

“I’m not ready to go. I’m not. I have to make, I don’t know. Christ. I have to make sure everything’s all in order, that you,” she trailed off. “Before I go.”

“Don’t worry about me, okay?”

I reached to squeeze her hand, but she pulled away to put on an Elvis album while she could still read her phone. Right as the trip came crashing into me, she glanced over real calm, eyes shrinking and growing in her face. “It’s catching up to me. But it happens, right? To all of us?”

She let me squeeze her hand, and I let the silence answer, the hum of the fridge, the crooning from the album. It all engulfed us right there on the carpet, and just as my sense of both space and time withered, mama’s front door groaned open. Had Tarrick come by? No, the fingers curling around the door were too white, not his deep brown, and I squeezed mama’s hand, so afraid I couldn’t move. She gripped mine back, and we sat dumbstruck as none other than Elvis himself stepped through mama’s front door.

He didn’t glance at us, just walked straight through behind the half wall and into mama’s kitchen. Like a photo of The King himself, Elvis stood in the center of the frame, fiddling with her juicer. This wasn’t old Elvis, back from the dead or something. No. This was young Elvis, hot Elvis, Elvis in his prime, the 1950s King in living, pulsing color. Younger than me – and younger than mama by a longshot – his shirt was open at the neck, revealing supple skin at the hollow of his throat.

Holding the masticating auger up, Elvis finally looked at us, straight through the postcard frame of the half wall, and said, “This is a nice juicer you got, momma.”

Mama said nothing, staring straight ahead at him – or at least, it looked like she was from the corner of my eye. I couldn’t quite peel my eyes from him. He chuckled and kept assembling her juicer.

Oh my God – was Elvis … God? And if so, was streaming his music and performing drag impersonations worship enough? By loving him, was I helping usher him back into existence, like some Roko’s Basilisk situation? Was I doing enough in the face of this returned deity?

Elvis tossed his head back and laughed. “Woah there, woah there, slow your rail, Satnin. I ain’t God, just a,” he gave up on assembling the juicer and posed, one arm above his head, “dimension surfer. Popped right out a black hole.” He wandered to the doorframe, revealing his whole body, and posed with his hips akimbo and his arms side to side, like he was gyrating on a surfboard, pinky rings glinting from the lamp behind me. His dress shoes, the kinds that are white on the tips, shone too.

“I’m just here for a good time, momma.” The way he said “momma” really had that “o” in it, so unlike the way I said “mama,” all made of breezes. His was thick as syrup, as thick as his slicked-back hair. Elvis’ smile dropped in sync with his hands, and that’s when I caught the hints of frown lines already forming in his young face.

“Now y’all look here. I’m realer’n flesh and blood.” Crouching down in front of us, he drenched me in his smell of coffee, of outside air, of someone else smoking a cigarette beside him. If cozy had a smell, that would’ve been it. He was so close I could’ve reached out and touched his perfect coif, but I didn’t, and to this day I regret that I didn’t, but at the very least, he grabbed our hands. My God, how mine tingled. The light of his hand spread through mama’s, their energy bird-calling back and forth in a frequency I could only half-catch.

His eyes this close up made it clear: this Elvis was something other than a human man. God? Couldn’t he be God? Smiling at me, he shook his head, a little sad. “No, honey. Not a single god out there in the whole wide megaverse, least not the kind you’re thinking of. Shoot, if I’m God, then so are you. Darlin’, I’ve been traveling, bouncing worlds and universes, time. I’m freer now – whatever ‘now’ is – than I was when I was on earth, why, freer than I ever was in this very city.” Glancing around, he seemed to see straight through the walls and out into Vegas. “My, how it’s changed. But then, things are always changing, aren’t they? And always staying the same.”

Right then he looked nothing like a human. Not with his eyes swirling like the Milky Way on a country road at night. Buttoning that gaze to mama, he said, “Like you’re about to change. From life, into death. Just as simple as changing shirts; one black hole to the next, momma.”

Finally I could crane my neck to see her face, tears tangling in her wrinkles as she nodded in vigorous little bobs. She knew something I didn’t, saw some weather pattern I’d never grasp until I was teetering on that precipice myself. So casual, Elvis shifted on the balls of his feet, and when he lifted the corners of his mouth, the twinkle in his eyes drowned out the galaxy behind them. He was suddenly just another young man again, flirting with his aging fans. “That’s a good record you got playin’.”

Of course it was. It was his first one. He squeezed our hands one more time before standing – his knees actually popping – and returning to the front door.

“I’ll see you,” he pointed right at mama, one hand over his head, the other by his waist, “on the other side. Let’s hop some black holes together, hey, pretty momma?”

Not waiting for an answer, Elvis walked out the door, turning the knob to keep it from making a sound. A half-second later, I opened my eyes, lying on the carpet, mama’s popcorn ceiling waving above me. My bones still sang from the pressure of his thumb against my right hand.

“Were you there? You see that?”

She shook her head, crying, not looking my way, whispering, “Okay, okay.”

We didn’t talk ‘til I was leaving and she pulled me into a hug, holding me tighter than she’d done since I moved to Vegas. “I’m so sorry, honey. I’ll love you forever and ever.” Letting me go, she scrubbed her eyes with the heel of her palm. “I, I gotta be alone, alright?”

In the days that followed, whenever I tried asking if she’d seen him, she slithered out of answering. All she said was she never wanted to do shrooms again. For some reason, I couldn’t tell Tarrick about what had happened. I don’t know. Guess I wanted to share something with mama, to be the right person for something in her life, just this once.

When she finally died, it was as if she’d been dissolving for a long time, becoming the yellow kind of pollen that dusts every windowsill in the South. You could say she gave up, but that wouldn’t have been right. It was more that she was fighting like hell for the natural progression of her soul.

The night after her funeral, I sat on the couch next to Bodie, whose fur had mostly grown back, and checked my newsfeed for the first time in days. Right there at the very top sat a headline that made my hand bones tingle. “Black Hole Sings Elvis?”

Heart thumping in time to the rockabilly of mama’s bygone heart, I clicked it. As I read, fat tears gathered at my chin and dropped in my lap. Somewhere deep in space, a black hole had sung out on the very day mama had died, warbling the unmistakable first four bars of “Can’t Help Falling in Love with You.”

Setting my phone down, I went into the bedroom where Tarrick read, and finally decided to tell him what happens when we die.

Copyright © 2022 by Nikita Andester