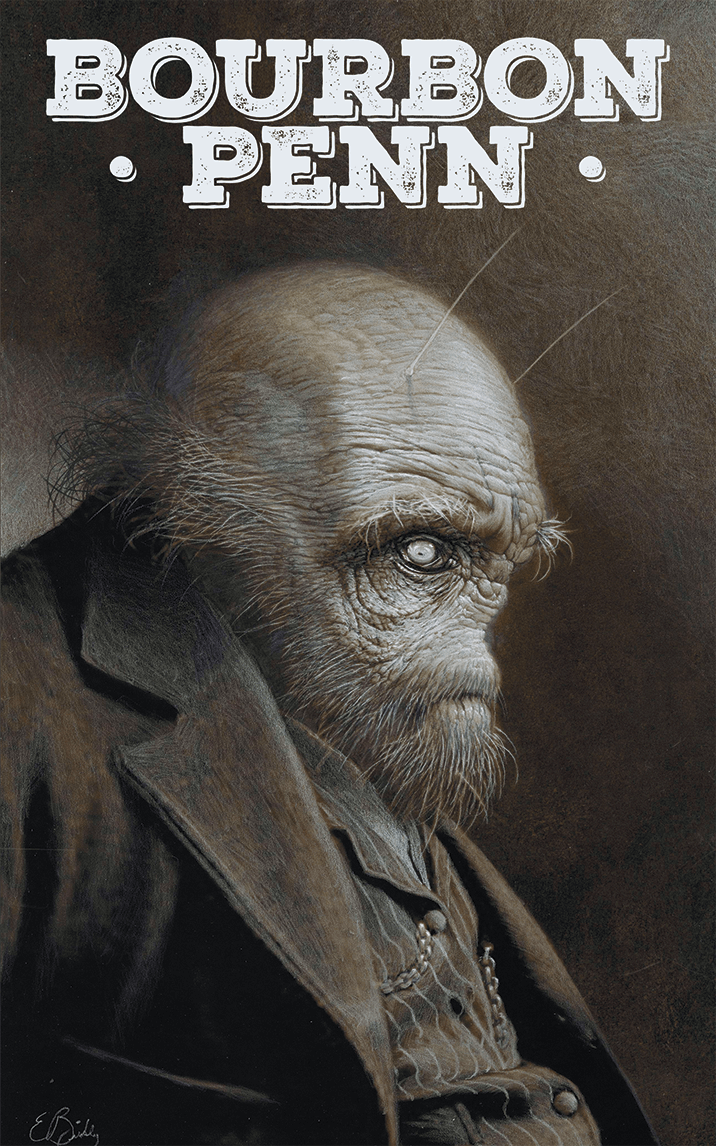

On the Hills, the Knitters

by Steve Toase

The knitters moved to the elephant five years after the plague ended. Sam and I watched them walk up past the village, carrying their possessions in rucksacks and wheelbarrows.

When the wheels caught on broken limestone, they helped each other, carrying the barrows between them over the rough ground.

The elephant wasn’t ours. We never asked for the three hundred foot knitted effigy to be dumped on the mountainside above the village. We didn’t put it there, but it had been sprawled across the rocks so long, longer than I’ve been alive, we felt it was part of the village. When the wind blew in the right direction, we smelled it in the street, the decay of the wool rotting in the summer sun like dead lambs. Sometimes lengths of orange yarn floated down the slope to catch in the gutters. As kids, we collected the strands and wove them into bracelets, telling ourselves that the elephant would protect us from evil, though we never knew what evil it could defend us against. Exchanging them and wearing them around our wrists as friendship bands.

We were offended that the knitters never asked permission, not that it was ours to give. The lack of etiquette that none of us really cared about put a distance between us and them.

When we were kids, we’d dare each other to spend the night inside the elephant. Sam and I did it one summer when we were 11. Or we told people we sheltered within the woollen corpse, when we really sat outside rather than shelter under that decaying orange skin. I still remember sitting high above the valley, looking at the lights in the village and listening to the elephant shift in its decomposition. Maybe we felt the knitters were taking part of our childhood away.

• • •

The first time they came down to the village for supplies, no one spoke to them. We all know each other. We’ve all been to each other’s weddings and funerals. The knitters would have stood out anyway under normal circumstances, but the way they dressed? All their clothes were woollen, bright-colored yarns knitted into patterns that seemed to have a meaning we could never understand. Even their shoes were felted and fitted, torn to pieces by the limestone. We got used to seeing blood on the paths, though it never seemed to bother them. They left scabbing trails along the shop floors that did not shift no matter how much we scrubbed them.

We were sat on the village green when they first spoke to us. Sam and I were sharing a bottle of Thunderbird and watching the sky change. Somewhere in the distance a radio played in one of the houses, just painting the air with music.

Three of the knitters stood around us, silent as the elephant decaying on the hill. We sat up and shielded our eyes from the sun, waiting for them to speak first. They did not.

“What do you want?” Sam said, climbing to his feet, hands shoved deep in his pockets.

“We need to buy some wool. Where can we buy some?”

“Nowhere around here,” I said, standing up beside Sam.

“We have money,” the oldest girl said. She wore a jacket knitted into multicolor panels, her plaited hair held back by a thin length of crochet.

“There’s nowhere to buy any,” Sam said. While we were talking the other two knitters had moved to either side of us. We stepped back, knocking over the bottle of Thunderbird, watching it seep into the worn grass.

“Our sheep will be here soon. We just need to make some repairs.”

“No one around here has any wool to give you.”

She reached out her hands. I flinched, but Sam let her grip his palm.

“Thank you anyway.”

They walked away and left us searching through our pockets for more coins to buy more Thunderbird.

• • •

Over the next few weeks, their outfits became more ragged and the amount of elephant stuffing clogging the gutters seemed to increase. We wondered if they were destroying the sculpture. Harvesting it for their own use. Then their sheep arrived and they penned them on the village green.

We just watched as the trucks drove down the narrow streets and unfurled ramps, the herd of animals quickly chewing up the pristine grass. The drivers began to erect hurdle fencing around the flock, paying little attention to the gathering crowd of us villagers. Sam’s dad walked up to one of the deliverymen and grabbed his arm, until he saw the man’s expression.

“You can’t leave those here,” he said. “They don’t belong here.”

The driver climbed into his cab and passed over an invoice.

“Delivery note says to bring them to the village, so we brought them to the village.”

“But they’re not meant for us.”

“Don’t care who they’re meant for. They’re delivered.”

“Don’t you need someone to sign for them?” Sam’s dad said, looking once more at the paper in his hand.

“Doesn’t need a signature. They’re delivered. My job’s done.”

“Must be for those incomers up the mountain. You need to take them up there.”

The driver called over the others and pointed up the narrow track. They shook their heads and laughed at Sam’s dad. I think that was the moment when things went really bad.

Later that day the knitters came down and herded the animals up to the elephant. Some of the men had been drinking all day and came out of the pub to shout abuse at them, but it was ignored. You could see the knitters’ point of view, but somehow it felt like everything was going to get worse.

The next day the sheep were wandering back down the hill. Several had fallen to smash to pieces on the rocks. The knitters came down to gather them back. They said nothing. Made no attempt to blame anyone or confront anyone. Just walked around in silence gathering in the animals. We noticed that most of the creatures had already been shorn, and soon after we saw the skeins of wool dyed and left to dry on wooden racks along the cliff edge. Those were the next target.

It started with slashing the yarn one night, the next pushing the racks to shatter where the sheep still lay rotting. No one confessed, even among the closed conversations happening behind the village’s closed doors. The next morning we looked out of our windows. The knitters stood in the streets, clumped together in groups with a single person in the center. We got up to leave our houses, go to our cars, the newsagents. We watched them, waiting for attack, but they did nothing. They stayed in their little clusters and did not retaliate.

Shame tastes of salt and sweat and we all shared it that morning, because we knew we were all complicit. And yet shame does strange things. Some people, it makes them prostrate themselves on the floor, begging for forgiveness before the universe takes retribution. Others it makes them double down. Bury the shame deep with layers of violence. After that morning I knew which way the village was going.

When Callum stepped up to the group of knitters on the village green, I was certain he was going to offer his hand in apology. To reach some kind of agreement. An accord. The only hand offered was a fist. The knitter was an older man, maybe a decade older than Callum, and it took four good punches until he fell to the green, scuffing up grass and mud as Callum stamped on his hands and legs, kicking him in the stomach and back. No one stopped him. Not the other knitters, not my fellow villagers and not me, and in those few moments we all became complicit.

When he finished, Callum walked back to his house and slammed the door as if sealing himself away gave him some solidity or purchase on the decision. On the green, the knitter lay bleeding, and none of his community went to pick him up. We could have left, gone back to our own houses. Instead we watched as he first pushed his swollen hands into the dirt, then dragged his knees up under him, and finally stood. Only once he was upright did the other knitters go to his aid. I caught his eye, and looked for anger in his expression, but there was none. There was no rage or desire for vengeance. Just sadness as if something had been lost, as if a mutual respect that could have worked toward something bigger had evaporated. Something better had bled out of that one man’s wounds.

They left then, carrying him back up the path, the rest of the men, women and children walked behind him. What happened that day transformed us as much as him. A boundary had been crossed and from then on things could only escalate.

• • •

The plague had devastated the moors. Taken three out of every ten of us, and left many others with scars as deep as any quarry. We went from communities of workers to cemetery villages haunted by the living. We just wanted to grieve in private. The elephant on the hill and the knitters it attracted gave us no chance to do that.

More came over the next few weeks. We did not know if this was planned, or if they sent out messengers to bring their people to them. Every few days a group of twenty or thirty would arrive, two or three families, and walk the foot-shredding path to the elephant.

We let them pass, watching them in silence. They were not cowed or apologetic. Or fearful. They paid us no attention whatsoever and instead ignored us as they walked through our streets to make their way to their new community. At night we saw their fires on the hill and heard their singing on the air, but when they saw us they never spoke unless spoken to, and that was rare.

One day Sam and I were sat on the benches drinking when a group were cutting across the village green. Worse for wear, Sam finished his Thunderbird and ran over to the group, bottle held low. I followed him, unsure what I was going to do if he lost control. Stop him or follow him. He grabbed the sleeve of a woman in her forties, stretching the red and yellow wool, close stitching revealing the holes as it deformed.

“Why there?” He said, holding on until she turned to him. “Why are you going up there?”

“We’re going home,” she said in a soft voice.

“And where’s home?” Sam continued, the words slurring so much I couldn’t tell if it was with anger or alcohol.

She pointed up the hill, and unhooked his fingers from her jumper.

“Home is up there,” she said, and carried on walking to catch up with her traveling companions.

“Forget about them,” I said to Sam. Two hours had passed and his silence had deepened with each bottle.

Instead of answering, he looked up the slope. Somewhere out of sight they were singing and the flames of their fires smudged the sky.

Pushing himself to his feet, he walked in the direction of the hill path.

“Just leave them alone. They’re not bothering us. They never pressed charges against Callum.”

Sam shook his head and carried on walking.

“Shouldn’t be there,” he said. “No right to just be there.”

I ran after him, trying not to stumble and fall, a task much harder as we started up the track. Even with our outdoor shoes on, the limestone cut through to our feet, and more than once I fell, tearing open my knees.

Taking such a direct route, there was no way to sneak up and that was never Sam’s intention anyway. The path opened up into the center of their camp, near the head of the elephant. He was there to show them something. An idea hooked inside his head. I stood behind him, not wanting to make it look like I supported everything he was about to do. No one looked up or stopped their conversations. In the firelight, the song carried on.

All around us people knitted. Some worked on small patches of cloth, others vast blankets, needles clattering in the dark. Even with the lack of light it was clear the work they’d done on the elephant. The repairs and replacements. I walked over and ran my hand over one of the ears.

“We’ve been busy.”

The man was the one beaten by Callum. His eye was still closed and the scar across his face suggested it would stay that way. I stepped back.

“We work in shifts to repair it,” he said. “Uses a lot of wool, but we have sorted that problem now.”

If I listened past the singing and the clattering of needles I heard something else. The sound of livestock a bit further out on the moor. Smelled them too. The reek of lanolin and shit.

“We didn’t want any more conflict with you all, so we arranged to have the sheep delivered to the other side of the moor and then drove the flock here.”

I glanced over toward Sam. He still stood in the middle of the camp, staring around and not speaking. Slowly he walked across to one of the wooden frames. I followed him. Closer now, I saw it was a loom, the woman sitting in front threading through the wool, her feet occasionally pressing the pedal to the dirt underfoot. Firelight reflected off the pattern.

“It’s beautiful.” Sam was entranced by the design, stepping closer until he was directly behind the weaver. She did not seem bothered by his presence and continued to work while he breathed sour alcohol over her shoulder.

In the firelight, the patterns danced. The design seemed to curve in on itself in a way that defined the threads as if the color bleached between them, I saw eyes staring back at me and the glistening of teeth. Something twisting and seething in the fabric. I felt myself focus more on the precise details, on the fibers in the wool that didn’t quite lay flat, snagging on those pressed down as the woman operated the loom. The sound of the wood shifting under her direction was setting the rhythm for the singing at the nearby campfires, and the voices were melding with the distant cries of the sheep calling into the darkness.

“What is it?” Sam asked. He seemed closer to the loom now, though he hadn’t moved.

“Home,” the woman said without turning, falling silent and letting her words be replaced by the clatter.

“You need to leave. The night is no time for outsiders to be here, and we don’t want your families to come looking for you up here.”

At first I thought Sam was not going to leave with me, and the sinking feeling returned. The sensation of watching someone disappear in front of you, even while they were still there. The sensation of a void opening up somewhere behind your ribs and all your organs compressing through it as their life drains away. We’d all experienced that during the plague so many times. I hoped I would never feel it again. I was wrong.

I grabbed Sam’s arm and dragged him toward the path. Drunk and tired, walking in the dark with only the vague light of the campfires above us, we struggled to stay upright, and arrived home with more scars and cuts than we left the camp with.

• • •

I called for Sam the next day, his mother sending me upstairs to his room. He sat by the window, staring up at the slope.

“Hangover?” I said, sitting on his bed and picking up a magazine to flick through. He didn’t answer and kept fixated on the distant hill, a slight edge of orange just visible. His hands were on the windowsill in front of him and kept moving over each other.

“You saw the pattern too, didn’t you?”

When we got back down, I’d walked home and finished the last of the beer in the fridge to block something out. Now I knew what, as the memory of those swirling teeth returned.

“What about it?”

“The spiral. It just felt so welcoming. Like inside there, somewhere, there was a place to go. A place to be.”

“How much did you have to drink last night?”

He turned and I thought he was going to hit me. I glanced down at his hand. I don’t know where he got the wool from. Some was the same orange as the elephant, dirty and gutter collected. Other strands were bright red and faded orange. I looked around the room, over the piles of clothes on the floor that I hadn’t really paid attention to before. The scissors lay on top of the jumpers, just enough cuts so he could unravel the stitches. Precise and economic. The unravelled wool was lying in a pile on the floor, slowly passing through his fingers as he knotted it to smaller strands. No design or organization, just activity. The friction had worn through his skin and several strands were coated in blood. He stared at me and all I saw was a dislocation somewhere deep inside.

I reached over and grabbed the wool from his hands.

“What are you doing?” I said, but he ignored me, reached down for another piece as he continued to stare out at the distant camp. I knew there was no way I’d get any sense out of him, so left him to whatever place inside his head he found more comfortable than the real world.

• • •

He went missing the next day. No one knew where to look for him. They gave it until nightfall, we often went walking in the fields and woods beyond the village, but he didn’t return. Leaving me behind was a worrying sign. We’d never done anything apart since school. When the sun set his family called the police. When the sun set I went off looking for him.

I didn’t think that my parents would be worrying too. Think we’d both been taken by the predators outside the village that they believed lurked around every urban corner and would drift into our community when they got bored with city streets. I didn’t think that they would get the police to search for me too.

The hillside path was treacherous in the dark, more so when I was sober it seemed. I dare not turn on a light in case someone below saw the glow in the dark and followed me. I had a pretty good idea where Sam had gone, and I had a pretty good idea what the rest of the village would do if they found out. I didn’t want that violence on my conscience. I didn’t want that violence on Sam’s.

Even though only a couple of days had passed since my last visit, the camp had changed beyond all recognition. All the wooden structures had been dismantled, and the air smelled of damp ash instead of campfires. There was no sound. No clicking of needles or looms. No singing or sheep calling out in the darkness. Nothing at all, apart from one single sound, quiet and muffled, coming from inside the giant woollen elephant.

The skin had been repaired with precise stitches, leaving only one entrance edged with torn stuffing. I prised apart the edges and eased myself in. First one foot, then the next, watching them disappear into the clouds of stuffing that pressed against my face as I moved further in. Inside the elephant, air was sparse and fibers coated my mouth, attaching to my tongue as I tried to lick my lips. The muffled breathing was more noticeable now.

Although the stuffing compressed me, it was clear a pathway had been carved through deep into the elephant. There was no light, and I had no torch with me. Instead, I pressed my hands through the most pliant spots, following the barely hollowed out labyrinth. The air around me smelled of copper and I felt the dampness of material brush against my skin. Once I no longer felt the air from the torn entrance, sweat began to drip down my face stinging my eyes, even in the darkness.

Somewhere deep inside the elephant I heard mewling, and wondered whether they’d slaughtered the sheep, left the lambs to bleed out in this humid compression. To let animals die in agony under the weight of the elephant’s stuffing took cruelty.

I tried to reach my hand to my face and wipe away the perspiration, but the pressure of the fibers against me held my arms in place against my sides. All I could do was walk on the route carved for me.

Had Sam walked the same route, putting foot after foot as he followed in the darkness, others walking behind him in their brightly colored jumpers and hats? Had he joined them before they left the hillside, following this path as an initiation into some kind of cult? Looking for meaning with strangers that the village never gave him? Looking for meaning that our friendship never gave him?

The mewling was louder now, the slaughtered sheep closer. The pressure around me distorted its cries. I stopped and tried to turn, but there was no way to pivot, no way to retreat. There was only forward. This was not just a passage through some discarded sculpture left to rot on a hillside. This was time and life and regret.

My throat clogged with the fine white fibers, tickling as they stuck in place, and without any choice in the matter, I coughed. There was no relief. I stopped and leaned forward to vomit them out of me, pressing fingers past my tongue. No matter how much I persisted they remained inside.

The weight around and above was a living thing now, shifting and flexing as I pushed through. More than once I wanted to turn. The compression did not give me that choice, just held me in place and forced me onward. Though uncomfortable and reaching for breath, I did not panic. The elephant was only three hundred feet long, and when I reached the end I could tear my way out and breathe fresh air once more.

Sam went of his own choice, and we always said we would leave the village and maybe not together. Since the plague not many visitors came, and not many visitors were welcomed elsewhere. Maybe he saw these strange quiet people as his only way to escape. Pausing, I closed my eyes and tried to remember his face. My mind doesn’t see well and I struggled to hold him in my imagination. I felt fibers stuck to my tearducts, and when I blinked they slid down my eyelid scratching patterns I did not want across my vision. For a moment I saw something precise and white floating around a black void. They snapped together, biting away the darkness.

I cried then. Not for Sam. Sam was fine. Sam was away. Found his escape with people I did not understand. I cried to clear my sight. I cried to see the way to go. I cried to return what little vision I had, but the elephant was in my mouth and my eyes and under my skin.

The screaming intensified, a rip of agony that did not let up. Closer now. Maybe I could at least put the animal out of its misery. How could people who offered no violence when attacked inflict so much cruelty on an animal? Not release it from its agony?

I felt the path guide me around, leading me deeper and deeper. The pressure from either side lessened, though the air stayed humid and heavy in its own way. I carried on as progress got easier. Somewhere ahead was a light. I had reached a way out. An exit from the embrace of an animal that had never lived, abandoned to rot on a hillside no one cared about. I readied myself to breathe fresh air, clear my mouth, clear my eyes, and followed the path’s last curve.

I was not outside. There was no route out of the elephant apart from one. The mewling leading me through the elephant was no lamb.

The knitters had stitched Sam in place, threads and knots going through his limbs, piercing his muscles and bone. Light filled the carved-out chamber, a glow coming from the wound bisecting Sam’s chest, lengths of crochet holding apart broken ribs. They’d taken his eyes and teeth and tongue, leaving just vacant wounds they’d stuffed with raw fleece. I moved closer, turning my head to vomit into the blood-soaked fabric beneath my feet.

The cavity the knitters had carved into Sam was ragged and ran from pelvis to just below his throat. I edged closer to see if there was anything I could do. Unhook his bones and fuse the wound in some way. That’s when I glanced inside him.

The hollow they had created within him wasn’t empty. Beneath the cut muscle the gap was filled with teeth, around the edge eyes. Not the eyes of predators, but the pleading gaze of the knitters, begging me to join them in safety, to just step past the blood and wounds and lower myself through the gap to a better world. To leave behind this place of plague and misery and starvation, and for a moment, just for a moment, as their songs drifted up to me and I smelled the sweetness of late night woodsmoke, I considered it. I considered stepping into the still-living corpse of my friend to escape a world that no longer had him within it. I caught sight of his expression as he strained to remain in the world, and I knew that if I left that there would be no one left to do what needed doing.

After I broke his neck I sat beside him until the light from within the wound faded. I don’t know what that meant, but my best friend was dead and it was because I thought it was better than leaving him as whatever they had transformed him into. Escape route or trap, he deserved better.

Once the chamber was in darkness, I followed the route back out, not caring if the fibrous stuffing suffocated me. Footstep by footstep I turned each turn and pressed past each blockade, until I reached the entrance once more.

• • •

They found me at the bottom of the hill-path with wounds I could not explain. A few days later, I was healed and so was the world.

No one was looking for Sam. No one remembered him as the place had scabbed over his absence. At first I thought the villagers were ignoring his disappearance to avoid conflict. Before that night they would have used any excuse to blame the knitters. To pick another fight. Now it was like none of them had ever existed within the world; Sam or the knitters.

I remember though. I remember the walk inside the elephant. I remember his mouth and sockets stuffed with wool. I remember those eyes staring at me from inside his chest, pleading with me to make my escape.

When the wind blows in the right direction it still smells of rot, but over the reek of decaying wool and old lanolin there is something else; the broken meat stench of my friend turned inside out as an escape for people we never made welcome. When no one else remembers I do, the air itself forcing me to see that escape again and again and again.

Copyright © 2022 by Steve Toase